CREATIVE PROJECT BY ASHLEY SIM SHUYI (’22)

No Path Marked

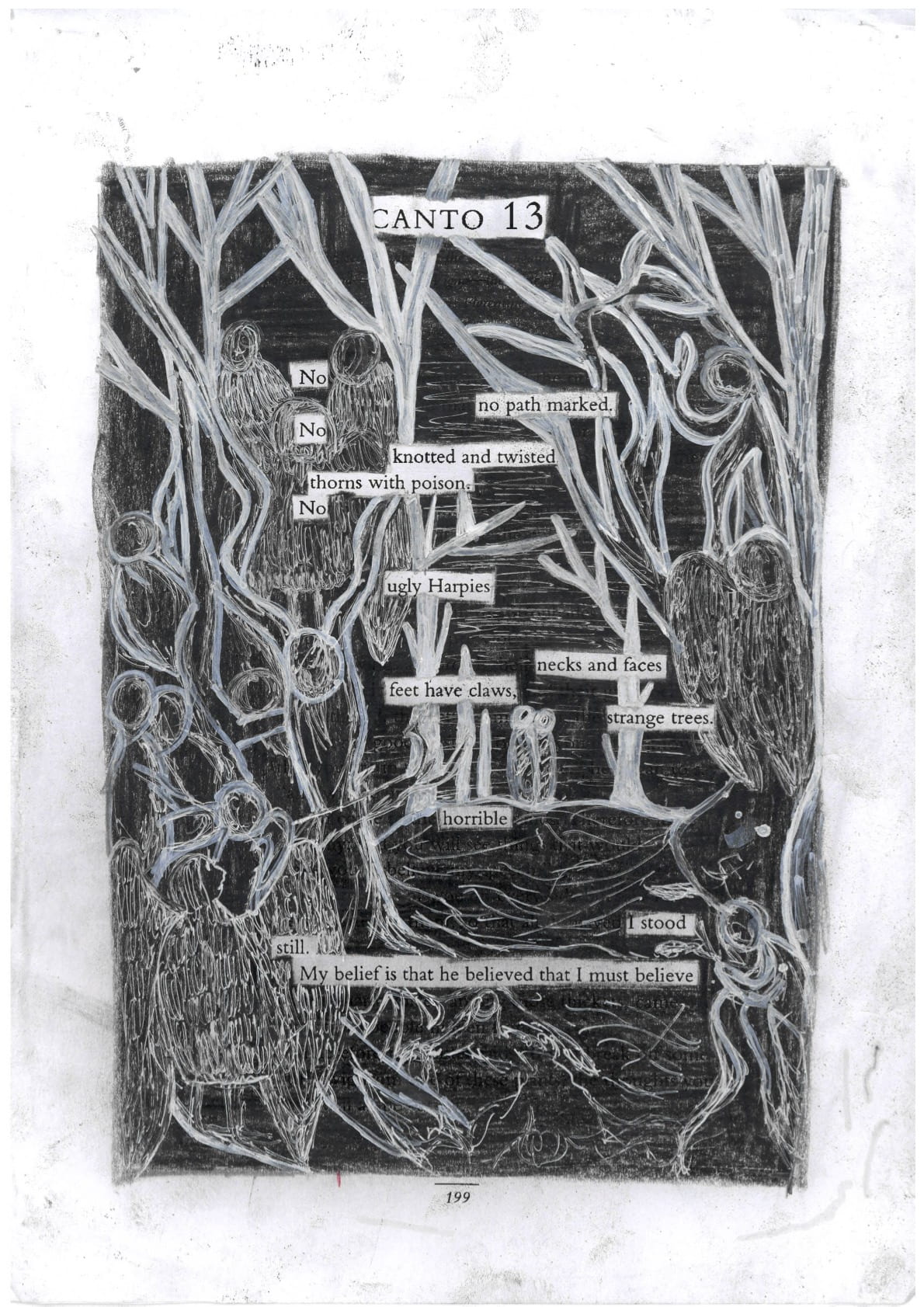

Visual Art / Literary Art (Blackout Poetry)

An Interpretation of Inferno

Death, Mourning and Memory in Medieval Literature (YHU3345)

2021

Artist’s Remarks

In the process of researching and re-imagining this canto, I hoped to draw insight into how this Canto fit into the entire text, particularly with regards to immortalization and memory. This is one of the many instances where Dante tempts the sinner into sharing their story through the promise of glorious immortalization, where the sinner’s real ‘truth’ is revealed. With this in mind, I am interested in Dante’s text as a strategy of liberation – not only is the sinner liberated from being merely identified by his sin through Dante’s recording of his story, but his soul is also emancipated from its roots in the tree. On another level, Dante himself is liberated from the despair of hell by writing and recording this story. Due to these complex intersecting layers of memory, history and stories, I saw a need to combine multiple art and aesthetic forms for this creative re-interpretation.

In Inferno, Dante appears to be a master of re-constitution and intertextuality as he draws inspiration from a variety of sources from Greek and Roman classics to his contemporaries. Similarly, black out poetry is an aesthetic form that draws heavily on similar ideas of reconstitution. In particular, I was drawn to Austin Kleon’s work Newspaper Blackout, which used the newspaper as a source material to create new and interesting work. When creating the blackout poem, I focused on both words that illustrated the scene as well as its shape. For example, I transformed ‘not’ (line 1, 4 & 7) into 3 Nos which linguistically and spatially mirrors the lamentation of the sinners. Surrounding the 3 Nos, I also grouped words together which not only described the scene but also came together in a shape that signified chaos and confusion.

Moreover, I was also intrigued by the medieval practice of creating palimpsests where one would recycle a piece of papyrus by washing off the original text. Inspired by this practice, I etched an illustration of the scene inspired by Gustave Dore’s illustration of Canto 13 over the blackout poem to create my own palimpsest. With Dore’s work as reference, I have used a similar composition of images, but I have changed the style of drawing, most significantly in my interpretation of the harpies and the shape of the trees. Compared to Dore’s illustration which is more realistic, I have decided to focus on shape and textures to create an atmosphere of chaos.

The title of my creative interpretation, no path marked, was largely inspired by the start of the poem “we entered a wood that no path marked. / Not green leaves, but dark in color, not smooth / branches, but knotted and twisted, no fruit was there, / but thorns with poison” (Dante 6.1 – 3). Even as Dante enters the forest where no discernible path forward is presented, the use of the negative “not” and the corruption of nature seen through the physical contortions of being “twisted” and the deathly “poisoned” nature of the branches underscores the unwelcoming, dangerous nature of the path ahead. I wanted to convey this sense of peril and precariousness through the misshapen lines and twisted shapes that the tree branches form surrounding the small figures of Dante and Virgil in the distance. A second central image in my drawing is the illustration of the harpies which are described as ugly creatures with human necks and faces intertwined with bird-like features. The Harpie at the bottom left of my drawing has the most distinct features, with a human face and textured wings, emphasizing the grotesque hybridity of the harpies watching over the sinners for eternity.

In his final encounter with Dante, Piero, the sinner who Dante speaks to, asks Dante to “strengthen my memory, languishing still beneath the blow that envy dealt it” (Inferno 6.76), a final attempt to forge his story into collective memory and break free from the prison of anonymity. Just as Dante re-inscribes Piero’s story by retelling the reason for his sin in hopes of emancipating his soul which was originally “uprooted” by Piero himself and sent to “[fall] into the wood” (Inferno 6.99) for eternal damnation, I hope that my additional layer of re-interpretation and re-constitution is able to further liberate the souls that remain on the seventh circle of hell, both from the pages of the text and also from the suffering in the literary hell of Dante’s Inferno.

REFERENCES

Alighieri, Dante. The Divine Comedy of Dante Alighieri: Inferno. Translated by Robert M. Durling. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996.

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

Austin Kleon’s blog can be found here: https://austinkleon.com/2014/04/29/a-brief-history-of-my-newspaper-blackout-poems/