CREATIVE PROJECT BY VIVIEN SIM (’24)

Love that Sends You to Hell

Visual Art

An Interpretation of Inferno

Death, Mourning and Memory in Medieval Literature (YHU3345)

2021

Artist’s Remarks

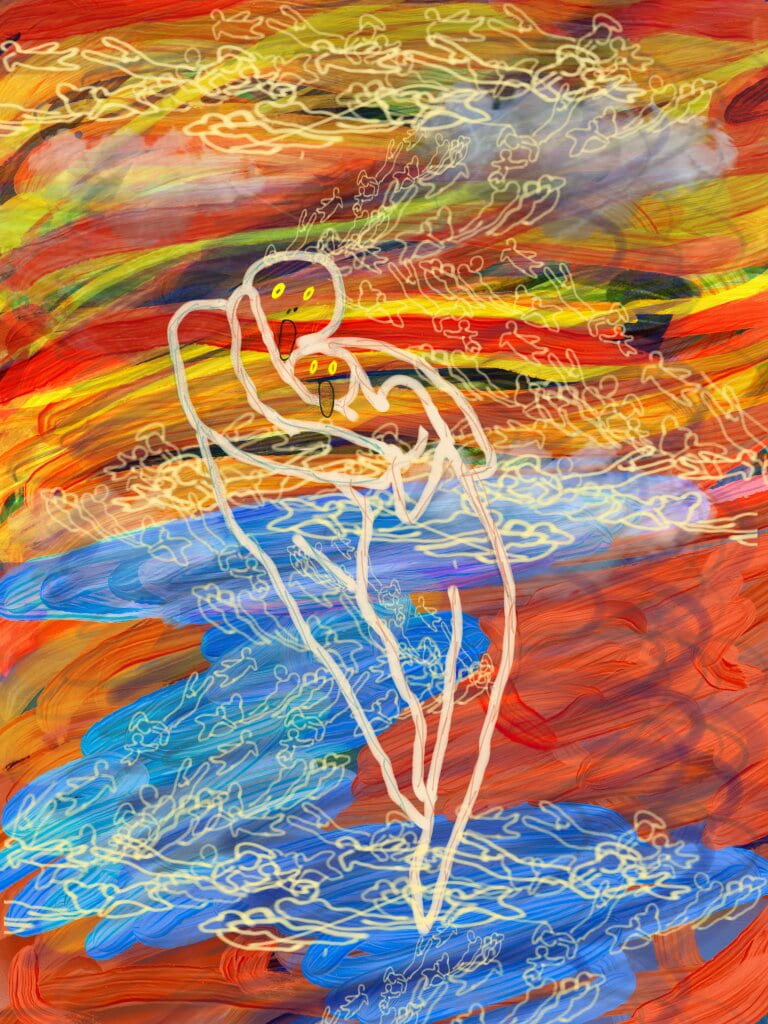

The bedrock of my impression of this canto rested in one line that stood out to me. It is when Dante seems to grant to the reader as he writes that he “came into a place where all light is silent” (Alighieri, 5.28), which means that we have left the realm where expressions of human knowledge can be relied upon to convey what we see. As a result, I chose to steer my creative interpretation in the direction of expressionism. In expressionist fashion, I aimed to depict subjective emotions rather than objective reality, which was appropriate in the narrative of Canto 5 given that Dante himself acknowledges that the human understanding of reality seems to melt away. I chose to distort and exaggerate what this subjective experience might be through widely contrasting and vibrant colors to create a jarring effect. Ironically, as I went against the literal meaning of light being silent (5.28) by the sheer visual intensity of the different extreme shades of red, blue and yellow, I was also able to convey the frenetic and crazed nature of this circle of hell. We can no longer trust in human instinct to visualise hell as we like it because human reality dissociates. Our only mode of experiencing and perceiving is by emotion, expressive and wild. Thus, I hoped that my choice in depicting Canto 5 in an expressionist style would convey a hallucinatory lunacy that demands that we leave common sense behind as we approach Dante’s work.

Subsequently, I chose to depict Francesca de Rimini and Paolo Malatesta in the form of Edvard Munch’s The Scream(1893), arguably is one of the most iconic pieces from the expressionist art movement. His art aimed to convey a moment’s panic and the distortion of reality and perception of that one moment. In similar fashion, I hoped to convey this frozen vision of panic and anxiety on the faces of Francesca de Rimini and Paolo Malatesta to indicate how Dante might see them. In Canto 5, Dante seems to oscillate between condemning them as “damned […] carnal sinners” (5.37-8) and the more charitable “ill-born” souls (5.7). Immediately, we see Dante’s internal conflict between his duty to denounce their sin, and his poetic predisposition to pity these souls and even share in their humanity. At this moment, I was moved by a quote by Victor Hugo: “You who suffer because you love, love still more. To die of love, is to live by it.” The human tendency to romanticise love becomes wrong and turned upon its head in Canto 5 as we see souls that are punished forever because they followed “[love], which is swiftly kindled in the noble heart” (5.100). If Hugo asserts that we ought to stand by love, Dante interjects that there are consequences. We are then confronted with the bleak question of how we ought to negotiate our relationship with love. The horror reflected on the faces of Francesca de Rimini and Paolo Malatesta is in the viewer’s perception of disordered reality, which might mean that this existential threat belongs to the observer as opposed to the souls.

It is easy to distinguish between love and lust, then, and object that because of this difference, our perception of love might still save us from Dante’s hell because it is not sinful lust. However, I reject this objection by portraying the figures of Francesca de Rimini and Paolo Malatesta and the sinners in the whirlpool behind as discombobulated masses to form intersections between love and lust. I did this because Dante seems to conflate lust with a forceful compulsion that overrides all other instincts: “Love […] seized me for his beauty so strongly that, as / you see, it still does not abandon me.” (5.103-5) Dante simultaneously desexualises lust and blurs the boundary of this new definition with our own concept of love that is powerful enough to drive and motivate us. By portraying the figures of the souls as scarcely human, I aim to rob them of all aspects of physical desirability. What remains are pairs of souls locked in protective embraces where they bend to accommodate the shape of each other. This is what I hope to convey in Dante’s “sweet nest through the air” (5.83). Yet, the romanticism of this becomes lost as the souls’ see-through outlines render full visibility to the backdrop of the vivid hell horizon as a stark reminder that they are still punished for this warped desire. Even though Francesca de Rimini and Paolo Malatesta seem to be in tender embraces, they may be considered lucky to suffer together because behind in the “cruel air” (5.86), others are not as fortunate—some are in suspension just outside arms’ reach of each other.

What I hoped to achieve with my portrayal of Dante’s Canto 5 is a true, vivid and existential threat to our own vision of love, even if it is done in a highly distortive art style. The paradoxical element of damning souls in love to be together, even if it is hell, also lends insight into how there is a higher form of love still, something beyond human understanding. This might be indicative in Dante’s main motivations of the Inferno as he soldiers through hell to get to heaven, where God resides. In this project, I hoped to convey and reckon with Dante’s idea of what subtle distinctions there are to love: distinctions between what might damn one to hell and its purest form that might afford us closeness to God.

REFERENCES

Alighieri, Dante, Robert M. Durling, Ronald L. Martinez, and Robert Turner. Essay. In Inferno, 86–99. New York: Oxford University Press, 1996.

Munch, Edvard. “The Scream,” 1893. National Gallery and Munch Museum. Oslo, Norway.