CREATIVE PROJECT BY SIMONE TAM (’22)

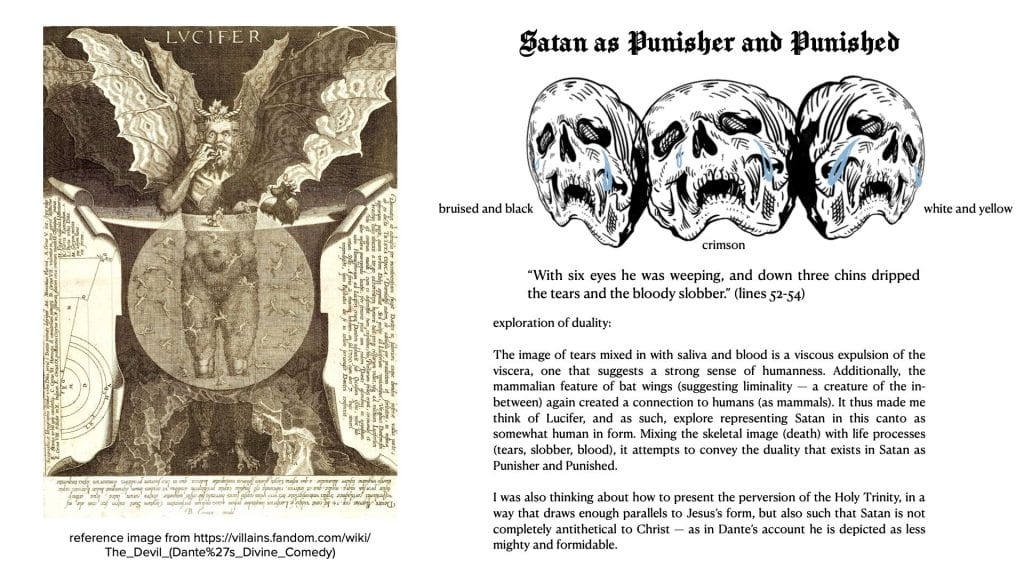

Go to Hell for Heaven’s Sake

Visual Art (Zine)

An Interpretation of Inferno

Death, Mourning and Memory in Medieval Literature (YHU3345)

2021

Your gateway into the world of medieval literature

Go to Hell for Heaven’s Sake

Visual Art (Zine)

An Interpretation of Inferno

Death, Mourning and Memory in Medieval Literature (YHU3345)

2021

Virgil and Dante Meeting Satan in the Ninth Circle

Visual Art (Painting)

An Interpretation of Inferno

Death, Mourning and Memory in Medieval Literature (YHU3345)

2021

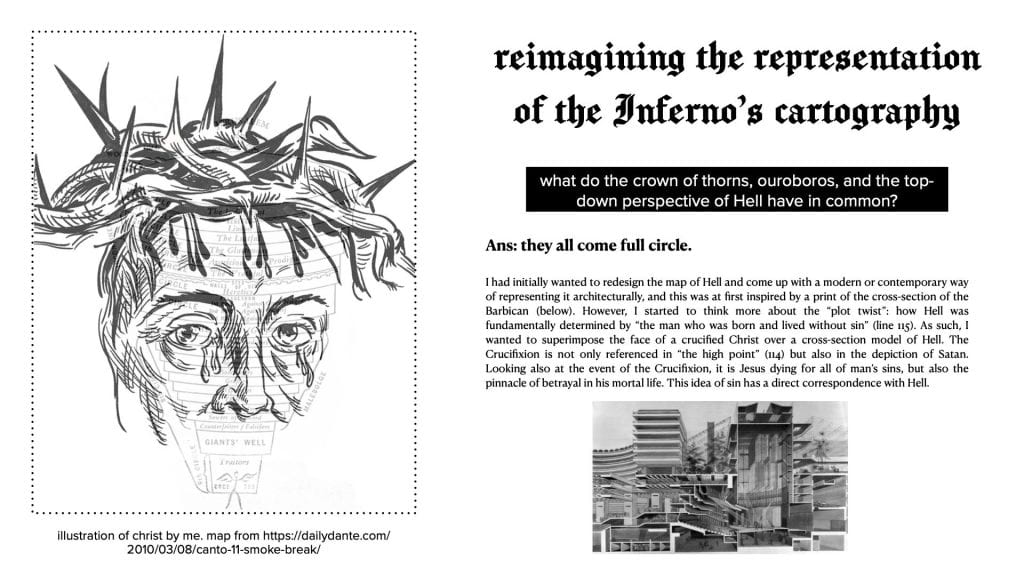

My decision to paint Dante’s and Virgil’s encounter with Satan in Canto 34 after their long and arduous journey through hell is rooted in my fascination with Satan’s unusual presentation. In the popular culture of the 21st century, Satan is portrayed in a seemingly glorified light and regarded as the ‘king of hell’: someone devious, scheming, and to be greatly feared. However, in Inferno, Dante brings to life an almost pitiable version of Satan in his work’s anti-climactic ending. The devil is regarded as “the emperor of the dolorous kingdom” (34.28), the most damned and pathetic sinner to be sentenced to eternal punishment in hell. I drew inspiration from Gustave Doré, one of the most widely known and celebrated illustrators of Inferno for my painting. Doré’s depiction of Satan in this sphere of suffering encapsulates the image that came to my mind upon reading this canto: one of absolute isolation and sorrow.

Perhaps the most immediately striking aspect of my painting is my usage of a muted color scheme. Despite painting with acrylic paints (as opposed to Doré’s black and white rendition), I used at most four colors to paint the scene of desolation beholding the pilgrims as they meet Satan: black, white, brown, and dark blue. I took this decision in an attempt to emphasize the bleakness and misery characterizing this canto – Dante and Virgil are in the depths of hell, so far removed from humanity that to use any brighter colors would seem a gross misrepresentation of their location in Judecca. I contrast this muted scene with the figures of Dante and Virgil, who are overlooking Satan – Virgil’s cloak is a golden yellow, and Dante’s is red. The choice to depict them in brighter colors is indicative of their humanity and innate goodness. They are merely passers-by, meant to stand out against this scene in a visual juxtaposition of the life and hope they embody. I painted Virgil’s cloak in a shade of golden yellow as a mark of his being the guiding light and truth leading Dante through the depths of hell. His characterization as Dante’s “leader” (34.8) and source of comfort (“there was no other shelter” (34.9)) attests to the intimate relationship the two have struck, where Dante relies wholly on Virgil to guide him through hell. Interestingly, the two faces of Satan visible in my painting are also his red and yellow faces. This ironic parallel of colors reveals the duality in the scene – Dante and Virgil are on a journey that will ultimately lead them to God, whereas Satan will never again be able to see the face of God.

In terms of my painting style, I did my best to present another dichotomy – Satan is painted smoothly, with colors blended well, as opposed to the intentional crudeness with which I painted his surroundings. Particularly in the cliffs and the landing, I employed a palette knife and a technique using the back of a paintbrush to create texture in the clashing of the roughly blended colors. In this depiction, I hope to capture the moral degradation present in their location of Judecca. Being the home of the greatest sinners, where Dante and Virgil encounter “so much evil” (34.83) in the face of Satan, I took the opportunity to represent the undoing of humanity and the breakdown of moral goodness in the breakdown of color and technique in the scenic elements surrounding Satan. On the other hand, my efforts at painting Satan smoothly, with colors blended perfectly and without a blemish on his skin, is in acknowledgment of the fact that Satan had once been the most beautiful of angels – “the creature who had once been beautiful” (34.17).

Concerning the scene I have illustrated, I painted the river and the cliff tops with a purposeful quality of obscurity. While Dante depicts the river that Satan is trapped in as frozen over, reflecting the scene above it clearly “like straws in glass” (34.12), I chose to portray the river as murky and polluted. In this pollutedness, I hoped to dramatize the effect of Satan’s sins and the other sinners in hell by implying that they contaminated the water. This establishes the damning effect of the sins – by being able to visually grasp the effects of the sins clouding up the river, the graveness of their transgressions is emphasized. In my artistic rendition, Satan’s reflection is barely visible; however, I have included Dante and Virgil’s figures’ reflections. This is to demonstrate that, even in the obscurity of the river, it retains its ability to reflect even a fragment of moral goodness through its defilement, emphasizing that Satan is too far gone to be saved.

In choosing to omit the other sinners’ bodies depicted in Doré’s art, I focus the scene solely on Satan and the pilgrims. In knowing that Dante and Virgil are hurrying to leave – indeed, it takes only 68 lines for Virgil to declare that “[they] must depart” (34.68) – and in seeing only their two figures in relation to Satan, one is confronted with Satan’s absolute isolation. He is trapped in the frozen river, immobilized and alone. Satan desired to be as powerful as God; therefore, his contrapasso is his complete loss of bodily autonomy and a voice. The dehumanizing aspect of his poetic justice invokes a sense of pity in the onlooker as one regards the slobbering, weeping, and wordless demon. I included a plaque inscribed with “abandon every hope, you who enter” (3.9) in my painting to echo the sentiment that greeted Dante and Virgil upon their entrance to hell in Canto 3. I intended for this to evoke a second meaning to the inscriptions understood only upon meeting Satan in Canto 34: in this pathetic rendition of Satan, it is he who has to abandon all hopes of freedom and glory in his eternal banishment to the depths of hell.

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

See Gustave Doré, “Satan” 34.34 here: http://www.worldofdante.org/gallery_dore.html.

The Inferno Postcard

Visual Art

An Interpretation of Inferno

Death, Mourning and Memory in Medieval Literature (YHU3345)

2021

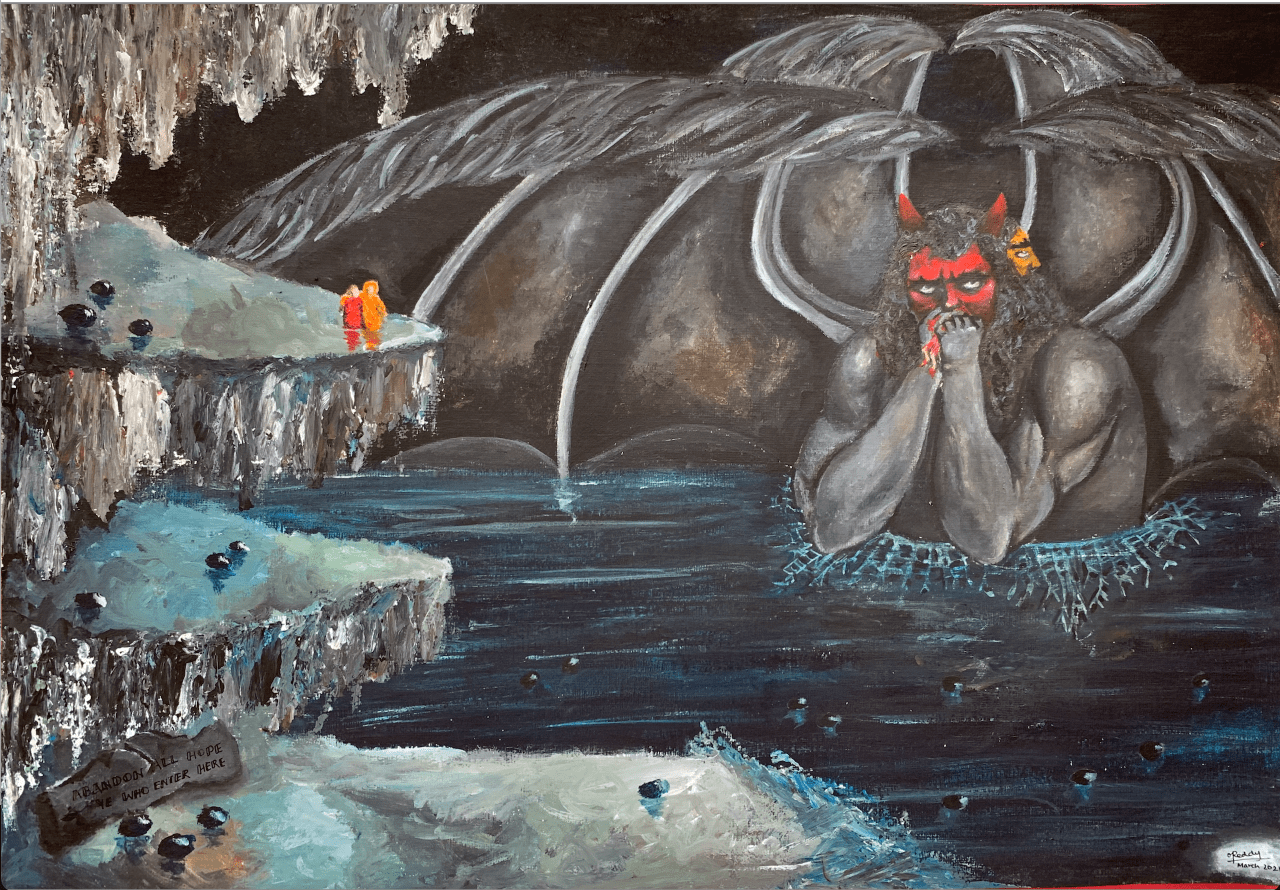

Drawing inspiration from Canto 34, this postcard evokes Dante’s completed imaginative vision of the afterlife. Viewing the postcard upright, we see Hell depicted on the left, beginning with the gateway to Hell. Instead of presenting each separate circle of sin, the choice to conflate distorted images of the Harpies, scabbing and suffering souls, the beheaded soul, and the reptile (serpent/snake) to make up Lucifer’s face expresses the accumulation of sin. Specific to Canto 34, the harshness of the black ink reflects Dante’s failure to illustrate the sight of Lucifer through speech. Flipping the postcard over, we see how the upside down and barely legible image of Satan represents the perverse nature of Satan’s three faces as a parody of God’s love, omnipotence, and omniscience. I chose to focus on the face that was positioned on the left to express the evil that continues to control the powerless Satan (34.44-5). For Dante, the source of evil that makes up Hell remains elusive, and Satan is but a figurehead who represents pure evil and who is not excluded from the poetic justice of the contrapasso.

Dante’s side profile is intentionally drawn using a mix of grey ink and pencil to present a stark contrast against the mass of black ink and dark grey highlighter. Together with Dante’s right eye looking up towards Heaven (which is more in focus than his left eye that is veiled during his witnessing of punishment and sin), the contrast expresses the commediain two ways: one, the Inferno as a parody of the divine, and two, Dante’s escape from Hell unscathed. Dante states, “I did not die and I did not remain alive; think now for yourself, if you have wit at all, what I became, deprived of both” (34.25-7). This statement implies a shift “from the experience of sin to the recovery of original justice” (577). This shift is also expressed in the canto’s play on time, space and geography:

On this side he fell down from Heaven; and the

dry land, which previously extended over here, for

fear of him took the sea as a veil,

and came to our hemisphere; and perhaps what

does appear on this side left this empty space in

order to escape from him, and fled upward. (34.121-126)

To achieve the same destabilizing effect on the viewers as did the canto’s manipulation of directionality (through phrases like “fell down,” “previously extended,” “fled upward” which require mental gymnastics on readers’ part), the intentional upright sketching makes illegible Lucifer’s face by focusing instead on Dante’s entry to Hell and his final escape, and one can only discern Lucifer’s haunting stare when flipping Dante’s portrait upside down.

Finally, the postcard’s interpretative nature expresses the commedia in the Inferno as an immortalization the word of the divine (audaciously so through the words of Dante the poet) that is at once elusive in its reference to the source of evil and clear in the call for recognition and rejection of sin. The absurdity of the postcard compels its recipient to view the world through Dante’s critical humour, albeit in another time and space.

REFERENCES

Alighieri, Dante. The Divine Comedy of Dante Alighieri: Inferno. Translated by Robert M. Durling. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996.

Dante’s Satan – A Moving Image

Animation

An Interpretation of Inferno

Death, Mourning and Memory in Medieval Literature (YHU3345)

2021

This moving image depicts Dante’s Satan as he is described in Canto 34. The piece features Satan with three heads, a pair of wings and a beating heart. The head in the middle chews Judas, the one on the left, Brutus, and the one on the right, Cassius.

On the three sinners: Brutus and Cassius’s sins mirror the bolgia of discord in how they betrayed Caesar, thereby causing political turmoil in Rome. Judas’ betrayal of Jesus can also warrant him a place in the third subcircle of the seventh circle reserved for those who were violent against God. As both Caesar and Jesus were foundational in shaping Italy’s culture and public consciousness, Dante ascribes an intense potency to the sins of those who betrayed them; thus they belong with Satan, the ultimate sinner who stood against God. To accentuate the nature of these sins even further, I borrowed the contrapasso elements from the ninth bolgia and the violence-against-God subcircle and weaved them into my animation. Cassius’s head is torn apart and put back together only to be torn apart again. This mirrors the punishment inflicted on Muhammed, Ali, and Bertrand de Born, who have their body parts torn and constantly separated from one another as punishment for sowing discord in the world. Brutus’s body is broken but is not being torn apart like Cassius’s because I wanted to represent the stoicism that he displays in Inferno — Virgil remarks that even though Brutus is writhing, he utters no words. (Inferno 34.66) The almost rigid nature of his body represents his choice to not show his pain. Dante perhaps respected Brutus enough to let his stoicism shine through even though he was being punished. There is smoke coming out of Satan’s mouth containing Judas. This is because Judas here is on fire. This reflects the nature of the punishment in the seventh subcircle, where flakes of fire fall on the spirits who were violent against God. Judas’s feet are sticking out because, as mentioned in Canto 34, his head is inside Satan’s mouth. (Inferno 34.63)

On Satan: I wanted to expound on the idea that we had discussed in class about Dante’s Satan as punishment but also the punished. I have captured the weeping and the “bloody slobber” from his mouth to portray him as someone as pitiable as the other three sinners. As for the background music, I reversed Sunn O)))’s song Báthory Erzsébet to get the unsettling, disturbing sounds that I added to my animation. I chose this track based on its review by someone I know: “What if Satan was in deep meditation? This is the noise that would emanate from His aura.” (Brahmecha, 2019) The track has a dark yet powerful energy and it seemed apt to me that in a space that punishes and disempowers Satan, the song’s reverse would play in the background.

REFERENCES

Alighieri, Dante. The Divine Comedy of Dante Alighieri: Inferno. Translated by Robert M. Durling. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996.

Brahmecha, Atharva. Thoughtssyncopated. 2019.

Sunn O))). Báthory Erzsébet. 2005.

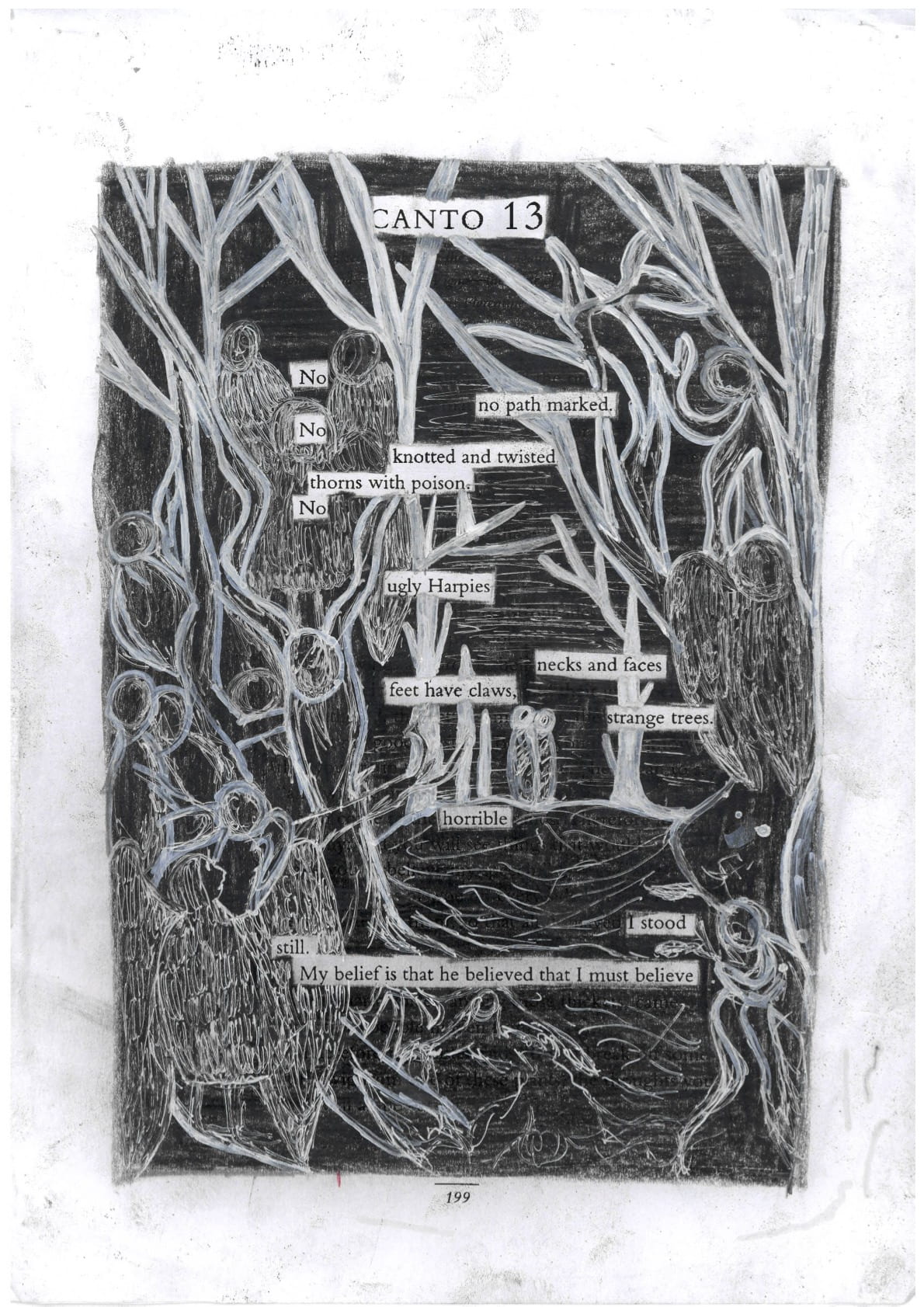

No Path Marked

Visual Art / Literary Art (Blackout Poetry)

An Interpretation of Inferno

Death, Mourning and Memory in Medieval Literature (YHU3345)

2021

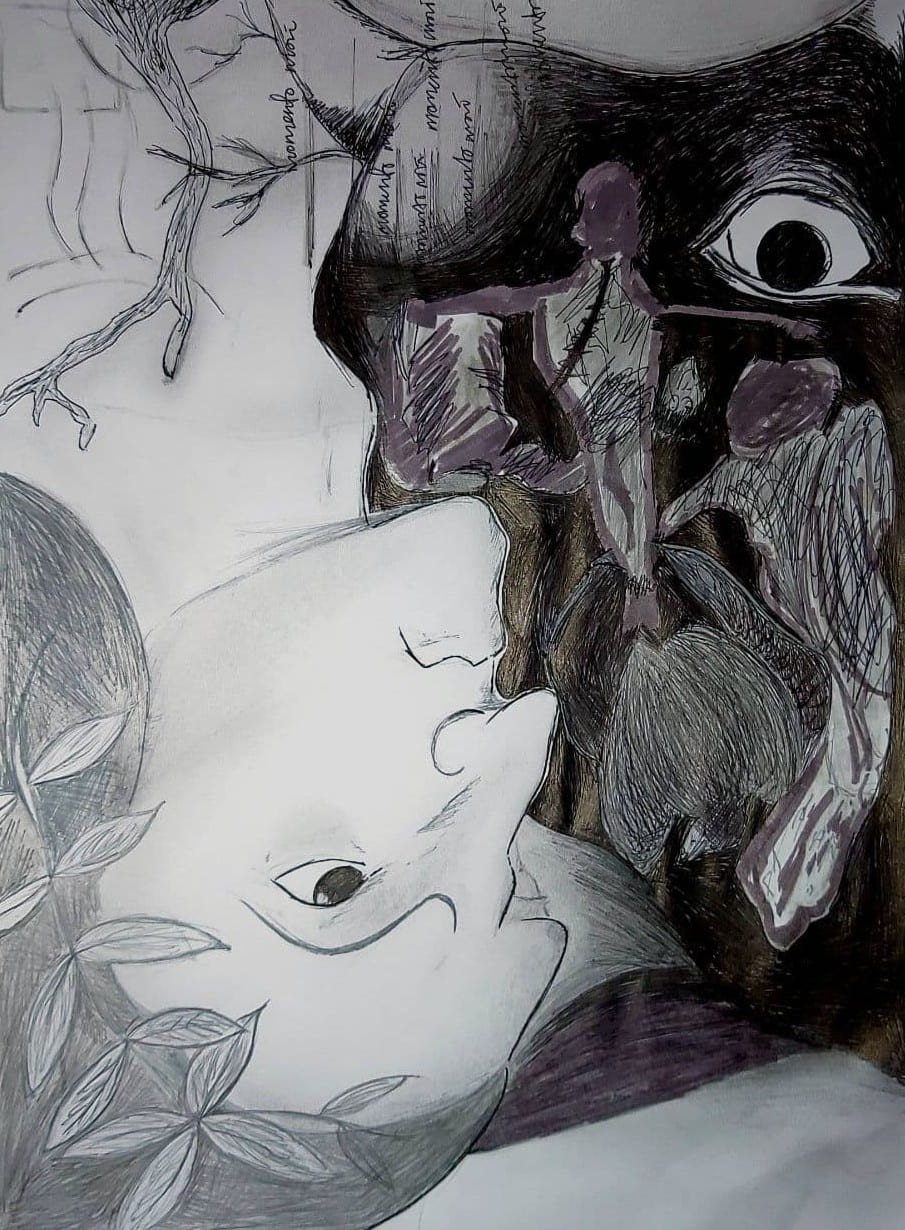

In the process of researching and re-imagining this canto, I hoped to draw insight into how this Canto fit into the entire text, particularly with regards to immortalization and memory. This is one of the many instances where Dante tempts the sinner into sharing their story through the promise of glorious immortalization, where the sinner’s real ‘truth’ is revealed. With this in mind, I am interested in Dante’s text as a strategy of liberation – not only is the sinner liberated from being merely identified by his sin through Dante’s recording of his story, but his soul is also emancipated from its roots in the tree. On another level, Dante himself is liberated from the despair of hell by writing and recording this story. Due to these complex intersecting layers of memory, history and stories, I saw a need to combine multiple art and aesthetic forms for this creative re-interpretation.

In Inferno, Dante appears to be a master of re-constitution and intertextuality as he draws inspiration from a variety of sources from Greek and Roman classics to his contemporaries. Similarly, black out poetry is an aesthetic form that draws heavily on similar ideas of reconstitution. In particular, I was drawn to Austin Kleon’s work Newspaper Blackout, which used the newspaper as a source material to create new and interesting work. When creating the blackout poem, I focused on both words that illustrated the scene as well as its shape. For example, I transformed ‘not’ (line 1, 4 & 7) into 3 Nos which linguistically and spatially mirrors the lamentation of the sinners. Surrounding the 3 Nos, I also grouped words together which not only described the scene but also came together in a shape that signified chaos and confusion.

Moreover, I was also intrigued by the medieval practice of creating palimpsests where one would recycle a piece of papyrus by washing off the original text. Inspired by this practice, I etched an illustration of the scene inspired by Gustave Dore’s illustration of Canto 13 over the blackout poem to create my own palimpsest. With Dore’s work as reference, I have used a similar composition of images, but I have changed the style of drawing, most significantly in my interpretation of the harpies and the shape of the trees. Compared to Dore’s illustration which is more realistic, I have decided to focus on shape and textures to create an atmosphere of chaos.

The title of my creative interpretation, no path marked, was largely inspired by the start of the poem “we entered a wood that no path marked. / Not green leaves, but dark in color, not smooth / branches, but knotted and twisted, no fruit was there, / but thorns with poison” (Dante 6.1 – 3). Even as Dante enters the forest where no discernible path forward is presented, the use of the negative “not” and the corruption of nature seen through the physical contortions of being “twisted” and the deathly “poisoned” nature of the branches underscores the unwelcoming, dangerous nature of the path ahead. I wanted to convey this sense of peril and precariousness through the misshapen lines and twisted shapes that the tree branches form surrounding the small figures of Dante and Virgil in the distance. A second central image in my drawing is the illustration of the harpies which are described as ugly creatures with human necks and faces intertwined with bird-like features. The Harpie at the bottom left of my drawing has the most distinct features, with a human face and textured wings, emphasizing the grotesque hybridity of the harpies watching over the sinners for eternity.

In his final encounter with Dante, Piero, the sinner who Dante speaks to, asks Dante to “strengthen my memory, languishing still beneath the blow that envy dealt it” (Inferno 6.76), a final attempt to forge his story into collective memory and break free from the prison of anonymity. Just as Dante re-inscribes Piero’s story by retelling the reason for his sin in hopes of emancipating his soul which was originally “uprooted” by Piero himself and sent to “[fall] into the wood” (Inferno 6.99) for eternal damnation, I hope that my additional layer of re-interpretation and re-constitution is able to further liberate the souls that remain on the seventh circle of hell, both from the pages of the text and also from the suffering in the literary hell of Dante’s Inferno.

REFERENCES

Alighieri, Dante. The Divine Comedy of Dante Alighieri: Inferno. Translated by Robert M. Durling. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996.

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

Austin Kleon’s blog can be found here: https://austinkleon.com/2014/04/29/a-brief-history-of-my-newspaper-blackout-poems/

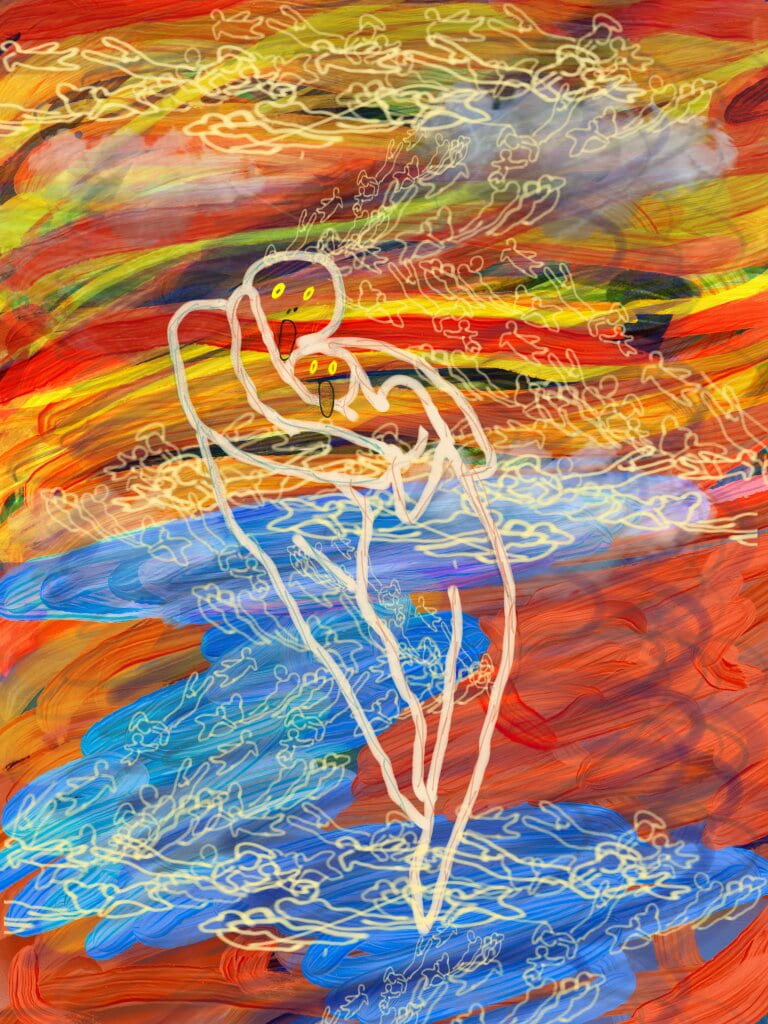

Love that Sends You to Hell

Visual Art

An Interpretation of Inferno

Death, Mourning and Memory in Medieval Literature (YHU3345)

2021

The bedrock of my impression of this canto rested in one line that stood out to me. It is when Dante seems to grant to the reader as he writes that he “came into a place where all light is silent” (Alighieri, 5.28), which means that we have left the realm where expressions of human knowledge can be relied upon to convey what we see. As a result, I chose to steer my creative interpretation in the direction of expressionism. In expressionist fashion, I aimed to depict subjective emotions rather than objective reality, which was appropriate in the narrative of Canto 5 given that Dante himself acknowledges that the human understanding of reality seems to melt away. I chose to distort and exaggerate what this subjective experience might be through widely contrasting and vibrant colors to create a jarring effect. Ironically, as I went against the literal meaning of light being silent (5.28) by the sheer visual intensity of the different extreme shades of red, blue and yellow, I was also able to convey the frenetic and crazed nature of this circle of hell. We can no longer trust in human instinct to visualise hell as we like it because human reality dissociates. Our only mode of experiencing and perceiving is by emotion, expressive and wild. Thus, I hoped that my choice in depicting Canto 5 in an expressionist style would convey a hallucinatory lunacy that demands that we leave common sense behind as we approach Dante’s work.

Subsequently, I chose to depict Francesca de Rimini and Paolo Malatesta in the form of Edvard Munch’s The Scream(1893), arguably is one of the most iconic pieces from the expressionist art movement. His art aimed to convey a moment’s panic and the distortion of reality and perception of that one moment. In similar fashion, I hoped to convey this frozen vision of panic and anxiety on the faces of Francesca de Rimini and Paolo Malatesta to indicate how Dante might see them. In Canto 5, Dante seems to oscillate between condemning them as “damned […] carnal sinners” (5.37-8) and the more charitable “ill-born” souls (5.7). Immediately, we see Dante’s internal conflict between his duty to denounce their sin, and his poetic predisposition to pity these souls and even share in their humanity. At this moment, I was moved by a quote by Victor Hugo: “You who suffer because you love, love still more. To die of love, is to live by it.” The human tendency to romanticise love becomes wrong and turned upon its head in Canto 5 as we see souls that are punished forever because they followed “[love], which is swiftly kindled in the noble heart” (5.100). If Hugo asserts that we ought to stand by love, Dante interjects that there are consequences. We are then confronted with the bleak question of how we ought to negotiate our relationship with love. The horror reflected on the faces of Francesca de Rimini and Paolo Malatesta is in the viewer’s perception of disordered reality, which might mean that this existential threat belongs to the observer as opposed to the souls.

It is easy to distinguish between love and lust, then, and object that because of this difference, our perception of love might still save us from Dante’s hell because it is not sinful lust. However, I reject this objection by portraying the figures of Francesca de Rimini and Paolo Malatesta and the sinners in the whirlpool behind as discombobulated masses to form intersections between love and lust. I did this because Dante seems to conflate lust with a forceful compulsion that overrides all other instincts: “Love […] seized me for his beauty so strongly that, as / you see, it still does not abandon me.” (5.103-5) Dante simultaneously desexualises lust and blurs the boundary of this new definition with our own concept of love that is powerful enough to drive and motivate us. By portraying the figures of the souls as scarcely human, I aim to rob them of all aspects of physical desirability. What remains are pairs of souls locked in protective embraces where they bend to accommodate the shape of each other. This is what I hope to convey in Dante’s “sweet nest through the air” (5.83). Yet, the romanticism of this becomes lost as the souls’ see-through outlines render full visibility to the backdrop of the vivid hell horizon as a stark reminder that they are still punished for this warped desire. Even though Francesca de Rimini and Paolo Malatesta seem to be in tender embraces, they may be considered lucky to suffer together because behind in the “cruel air” (5.86), others are not as fortunate—some are in suspension just outside arms’ reach of each other.

What I hoped to achieve with my portrayal of Dante’s Canto 5 is a true, vivid and existential threat to our own vision of love, even if it is done in a highly distortive art style. The paradoxical element of damning souls in love to be together, even if it is hell, also lends insight into how there is a higher form of love still, something beyond human understanding. This might be indicative in Dante’s main motivations of the Inferno as he soldiers through hell to get to heaven, where God resides. In this project, I hoped to convey and reckon with Dante’s idea of what subtle distinctions there are to love: distinctions between what might damn one to hell and its purest form that might afford us closeness to God.

REFERENCES

Alighieri, Dante, Robert M. Durling, Ronald L. Martinez, and Robert Turner. Essay. In Inferno, 86–99. New York: Oxford University Press, 1996.

Munch, Edvard. “The Scream,” 1893. National Gallery and Munch Museum. Oslo, Norway.

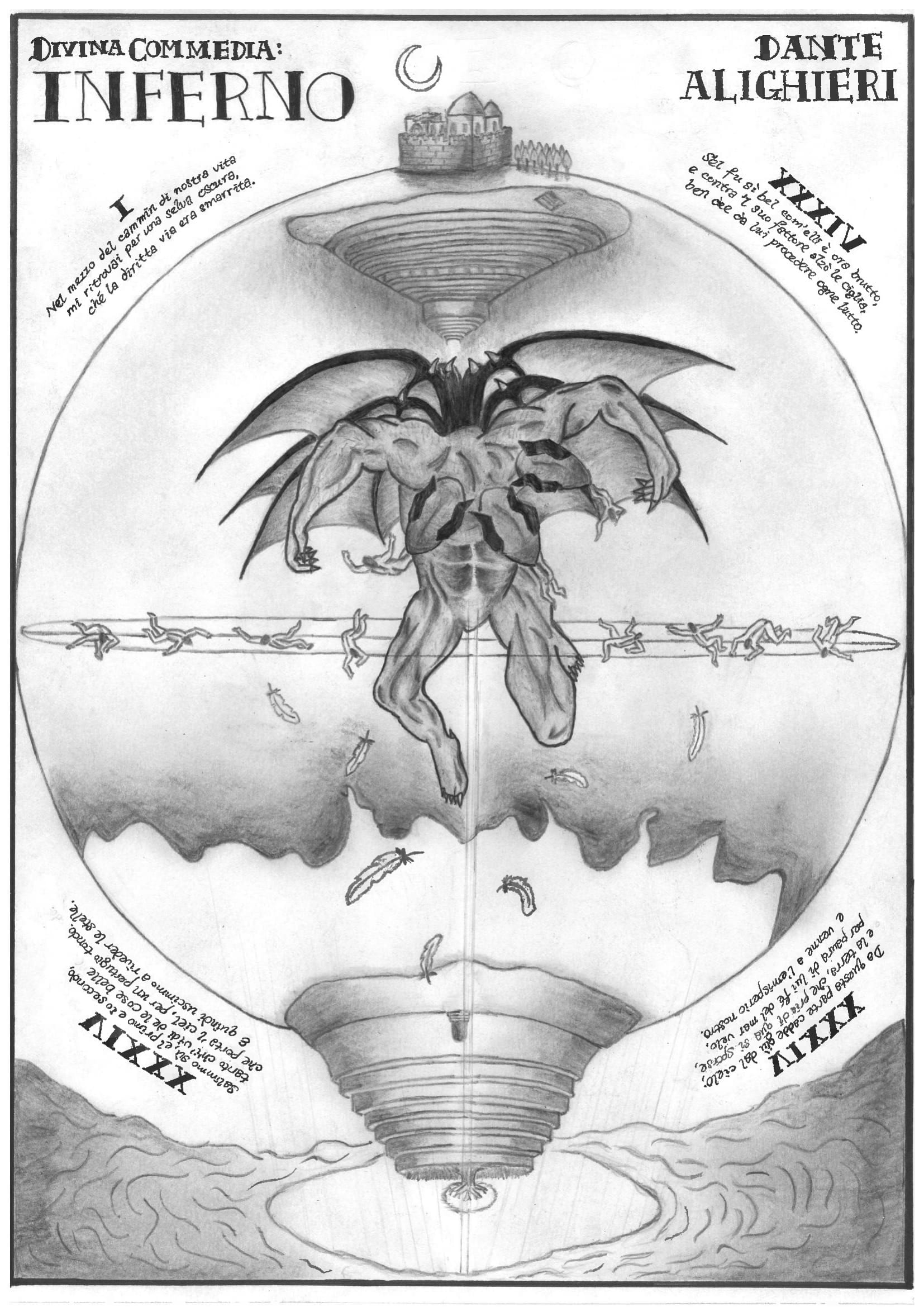

The Anatomy of Lucifer and the Universe

Visual Art (Drawing)

An Interpretation of Inferno

Death, Mourning and Memory in Medieval Literature (YHU3345)

2021

My creative interpretation for Dante’s Inferno is inspired primarily by Canto 34 (with elements of Canto 1 as well). Overall, I think what it illuminates about the text and Canto 34 especially is the general perspective of the world according to Dante’s theology, of how the journey through Inferno was possible in the first place (and why it was necessary), and it gives more insight into Lucifer, who was quite grossly diminished in the text.

The interpretation takes the form of a medieval manuscript page imitation, completed on paper entirely with pencil and ink, in black-and-white monochrome colour scheme. The imitation, done to pay homage to the Middle Ages and evoke its sense of history, is immediately visible with the black frame and labelling of the text’s title and author’s name in an olden-style typography. Choosing to imitate the artistry of a manuscript page also helps convey the grandeur befitting Dante’s tale, its genre, and its thematic / theological concerns. Meanwhile, the colour scheme is chosen to exude the solemn and serious mood of the text, and to play on the notion of “black and white” being indicative of good and evil, or morality in general. After all, morality (as determined by religion) is the core concern of the text. The monochrome scheme also makes the contrasts in shadings and gradients more visible, thereby allowing the art to seem more realistic.

The circle represents the boundaries of the mortal realm. Four quotes from Cantos 1 and 34 are written in accompaniment along the circle’s boundary, organised in clockwise direction, which forces the reader to flip the page upside down. This creates a dynamic in the page where two perspectives are possible, making the visual experience more interactive. The original Italian version of the quotes are chosen instead of the English version in order to remain faithful to the text’s origin and culture. For this very reason, the Cantos from which the quotes are picked are also indicated in Roman numerals instead of Arabic numerals. In addition, the use of Italian and Roman numerals points to Italy in general, the seat of the Catholic Church, and the Roman Empire, in doing so highlights their importance to Dante’s politics and his theology. The first quote comes from the opening of the text, the second from lines 34 to 36 (Canto 34) where the pilgrim exclaims the duality in Lucifer’s appearance (once beautiful but now ugly), the third from lines 121 to 124 (Canto 34) where Virgil explains the ingenious inversion of their perspective after passing Lucifer, and the fourth from the closing lines of the text where the duo climbed out of Hell and saw the skies once more.

At the top of the circle lies the moon, a human city, the dark wood which the pilgrim became lost in Canto 1, and the concentric landscape of Hell. These indicate where the pilgrim has come from in terms of both time and place. On the other side of the circle lies Purgatory, isolated from land (in accordance to then-contemporary belief that the southern hemisphere is covered in water, as mentioned by Virgil in Canto 34), and Heaven / Paradise, as hinted by the hole in the sky where light comes from (which also implies that the sun is somewhere there) and where the clouds appear gradually brighter.

The main subject, Lucifer, is enclosed within the circle. His size is exaggerated to a large scale to emphasise his being the heart of Hell and the pilgrim’s encounter with him as the climatic moment in Inferno. A second circle is drawn around his thighs to indicate the plane where he is trapped with sinners in wretched positions, as mentioned in Canto 34. Together, the circles and horizontal line separating the hemispheres puts Lucifer in a position as though he is being examined and his anatomy analysed for the reader of the manuscript page, an idea inspired by Da Vinci’s renowned Vitruvian Man drawing. Lucifer himself is depicted with a degree of artistic license. His possession of six wings is inferred from his being a former archangel; they now resemble (as indicated in Canto 34) those of a bat’s and they look like sails as well. If examined closer, there are thin hairs which are faintly visible all over his body (especially on his arms). His body’s hairy nature is downplayed to give more emphasis to the unnatural body posture and its bulging veins and muscles that seem almost painful. This is done to draw attention to his suffering (contrary to the image of him being a glorious ruler of Hell), as highlighted in Canto 34. The punishment of Lucifer is further enhanced with his heads lowered, as though he was weeping (noted by the pilgrim) and in shame. The lack of facial depiction also helps bring out the anticlimactic silence and lack of interaction in Canto 34, since without faces, no direct encounter is possible. The greatest human sinners as alleged by the pilgrim, are included, gnawed upon by Lucifer. The lack of visible mouths for Lucifer make the sinners appear almost like tongues, which evokes the imagery of the serpent, painting Lucifer as the greatest deceiver. The dark shading of Lucifer paints him as the embodiment of evil, yet the white space around him contrasts and brings out his paradoxical nature—that his existence serves to strengthen and reinforce the moral legitimacy and authority of the Christian God and His doctrines—aside from simply depicting the icy landscape of the deepest level of Hell.

When the manuscript is flipped upside down, the answer to Lucifer’s seemingly unnatural body posture is clearer. Paired with the superimposed drifting feathers, the motion of his fall from Heaven and grace is captured. This is something that I desired to flesh out the most from Canto 34, such that Lucifer appears to still be falling, and this motion is effectively immortalised. The feathers are those from his former archangel wings, drawn as such to indicate Lucifer’s past. The ray of light extended to Lucifer’s abdomen is the stairway to Purgatory and Heaven climbed by the pilgrim and Virgil. I chose to depict it as a ray of light so that the contrast between the darkness of Lucifer, Hell, and what was on the other side, could be made much starker and more evident. The sketchy pencil strokes that mark out the ladder conveys the uncertainty and fear about the journey that the pilgrim must undertake. The ray of light is drawn in a way such that the areas which it touches are somewhat whitened, and the sketchy pencil markings help to enhance its glow and allow it to shimmer, all to highlight the ethereal and strange nature of the pilgrim’s journey thus far from Hell, and beckons to what lies ahead.