CREATIVE PROJECT BY OSHEA REDDY (’24)

Virgil and Dante Meeting Satan in the Ninth Circle

Visual Art (Painting)

An Interpretation of Inferno

Death, Mourning and Memory in Medieval Literature (YHU3345)

2021

Artist’s Remarks

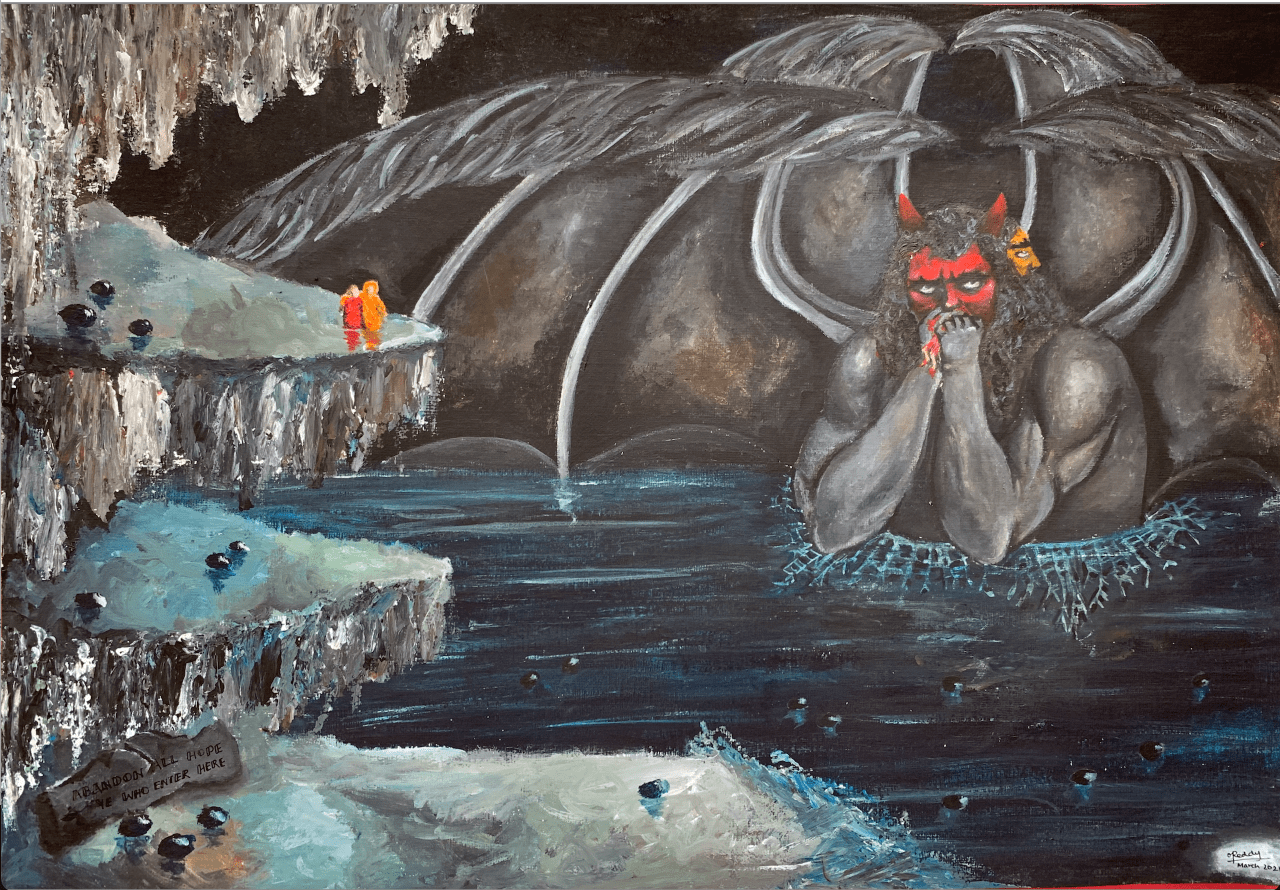

My decision to paint Dante’s and Virgil’s encounter with Satan in Canto 34 after their long and arduous journey through hell is rooted in my fascination with Satan’s unusual presentation. In the popular culture of the 21st century, Satan is portrayed in a seemingly glorified light and regarded as the ‘king of hell’: someone devious, scheming, and to be greatly feared. However, in Inferno, Dante brings to life an almost pitiable version of Satan in his work’s anti-climactic ending. The devil is regarded as “the emperor of the dolorous kingdom” (34.28), the most damned and pathetic sinner to be sentenced to eternal punishment in hell. I drew inspiration from Gustave Doré, one of the most widely known and celebrated illustrators of Inferno for my painting. Doré’s depiction of Satan in this sphere of suffering encapsulates the image that came to my mind upon reading this canto: one of absolute isolation and sorrow.

Perhaps the most immediately striking aspect of my painting is my usage of a muted color scheme. Despite painting with acrylic paints (as opposed to Doré’s black and white rendition), I used at most four colors to paint the scene of desolation beholding the pilgrims as they meet Satan: black, white, brown, and dark blue. I took this decision in an attempt to emphasize the bleakness and misery characterizing this canto – Dante and Virgil are in the depths of hell, so far removed from humanity that to use any brighter colors would seem a gross misrepresentation of their location in Judecca. I contrast this muted scene with the figures of Dante and Virgil, who are overlooking Satan – Virgil’s cloak is a golden yellow, and Dante’s is red. The choice to depict them in brighter colors is indicative of their humanity and innate goodness. They are merely passers-by, meant to stand out against this scene in a visual juxtaposition of the life and hope they embody. I painted Virgil’s cloak in a shade of golden yellow as a mark of his being the guiding light and truth leading Dante through the depths of hell. His characterization as Dante’s “leader” (34.8) and source of comfort (“there was no other shelter” (34.9)) attests to the intimate relationship the two have struck, where Dante relies wholly on Virgil to guide him through hell. Interestingly, the two faces of Satan visible in my painting are also his red and yellow faces. This ironic parallel of colors reveals the duality in the scene – Dante and Virgil are on a journey that will ultimately lead them to God, whereas Satan will never again be able to see the face of God.

In terms of my painting style, I did my best to present another dichotomy – Satan is painted smoothly, with colors blended well, as opposed to the intentional crudeness with which I painted his surroundings. Particularly in the cliffs and the landing, I employed a palette knife and a technique using the back of a paintbrush to create texture in the clashing of the roughly blended colors. In this depiction, I hope to capture the moral degradation present in their location of Judecca. Being the home of the greatest sinners, where Dante and Virgil encounter “so much evil” (34.83) in the face of Satan, I took the opportunity to represent the undoing of humanity and the breakdown of moral goodness in the breakdown of color and technique in the scenic elements surrounding Satan. On the other hand, my efforts at painting Satan smoothly, with colors blended perfectly and without a blemish on his skin, is in acknowledgment of the fact that Satan had once been the most beautiful of angels – “the creature who had once been beautiful” (34.17).

Concerning the scene I have illustrated, I painted the river and the cliff tops with a purposeful quality of obscurity. While Dante depicts the river that Satan is trapped in as frozen over, reflecting the scene above it clearly “like straws in glass” (34.12), I chose to portray the river as murky and polluted. In this pollutedness, I hoped to dramatize the effect of Satan’s sins and the other sinners in hell by implying that they contaminated the water. This establishes the damning effect of the sins – by being able to visually grasp the effects of the sins clouding up the river, the graveness of their transgressions is emphasized. In my artistic rendition, Satan’s reflection is barely visible; however, I have included Dante and Virgil’s figures’ reflections. This is to demonstrate that, even in the obscurity of the river, it retains its ability to reflect even a fragment of moral goodness through its defilement, emphasizing that Satan is too far gone to be saved.

In choosing to omit the other sinners’ bodies depicted in Doré’s art, I focus the scene solely on Satan and the pilgrims. In knowing that Dante and Virgil are hurrying to leave – indeed, it takes only 68 lines for Virgil to declare that “[they] must depart” (34.68) – and in seeing only their two figures in relation to Satan, one is confronted with Satan’s absolute isolation. He is trapped in the frozen river, immobilized and alone. Satan desired to be as powerful as God; therefore, his contrapasso is his complete loss of bodily autonomy and a voice. The dehumanizing aspect of his poetic justice invokes a sense of pity in the onlooker as one regards the slobbering, weeping, and wordless demon. I included a plaque inscribed with “abandon every hope, you who enter” (3.9) in my painting to echo the sentiment that greeted Dante and Virgil upon their entrance to hell in Canto 3. I intended for this to evoke a second meaning to the inscriptions understood only upon meeting Satan in Canto 34: in this pathetic rendition of Satan, it is he who has to abandon all hopes of freedom and glory in his eternal banishment to the depths of hell.

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

See Gustave Doré, “Satan” 34.34 here: http://www.worldofdante.org/gallery_dore.html.