| Category | Text |

| Form | Epic Poetry |

| Genre | Comedy |

| Author | Dante Alighieri |

| Time | Early 14th Century |

| Language | Tuscan / Florentine Vernacular (Italian) |

| Featured In | Death, Mourning and Memory in Medieval Literature (YHU3345) |

Inferno is an epic poem by Dante Alighieri, and is the first part of Dante’s Divina Commedia, of The Divine Comedy. The poem follows the pilgrim Dante’s descent into hell, guided by ancient Roman poet Virgil, whose epic poem Aeneid also explores the afterlife / underworld at some point.

REFLECTIONS AND ENGAGEMENT

The text of Inferno had evoked very different responses across the class. A good half of the class eventually produced creative projects inspired by the Cantos that they personally found particularly striking and memorable:

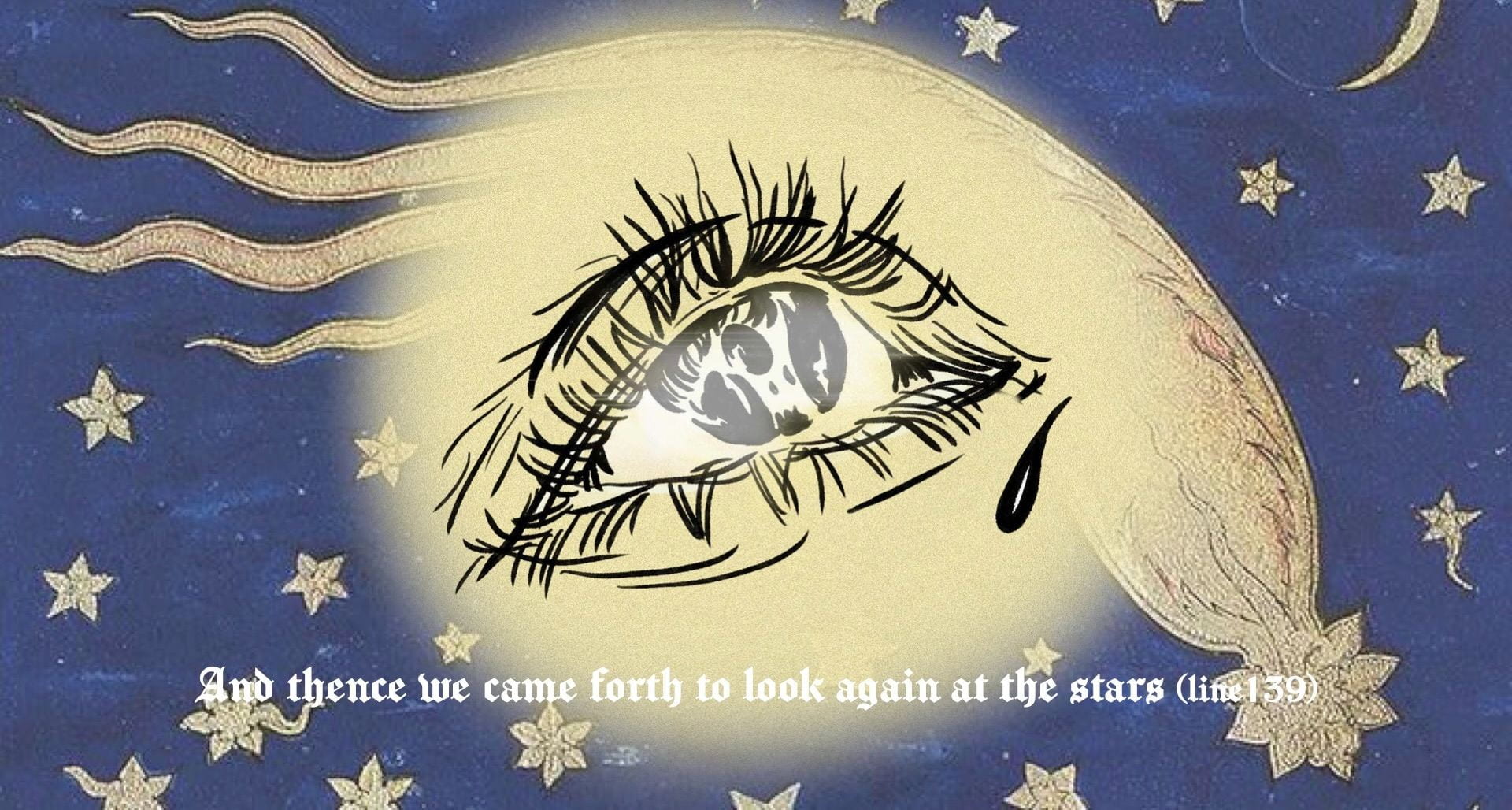

CANTO 5

In Canto 5 of Dante’s Inferno, the lustful are punished in a vortex of conflicting winds. This particular canto stood out to me because Dante is ambiguous in his treatment of the sinners who reside in this section of hell. He neither condemns them totally, nor does he absolve them of fault for giving in to their own desires. In this sense, Canto 5 demonstrates an obvious conflation between the figures of Dante the poet and Dante the pilgrim, as well as a true human weakness towards how we might come to negotiate our approach and position on types of love.

The bedrock of my impression of this canto rested in one line that stood out to me. It is when Dante seems to grant to the reader as he writes that he “came into a place where all light is silent” (Alighieri, 5.28), which means that we have left the realm where expressions of human knowledge can be relied upon to convey what we see. As a result, I chose to steer my creative interpretation in the direction of expressionism. In expressionist fashion, I aimed to depict subjective emotions rather than objective reality, which was appropriate in the narrative of Canto 5 given that Dante himself acknowledges that the human understanding of reality seems to melt away. I chose to distort and exaggerate what this subjective experience might be through widely contrasting and vibrant colors to create a jarring effect. I hoped that my choice in depicting Canto 5 in an expressionist style would convey a hallucinatory lunacy that demands that we leave common sense behind as we approach Dante’s work.

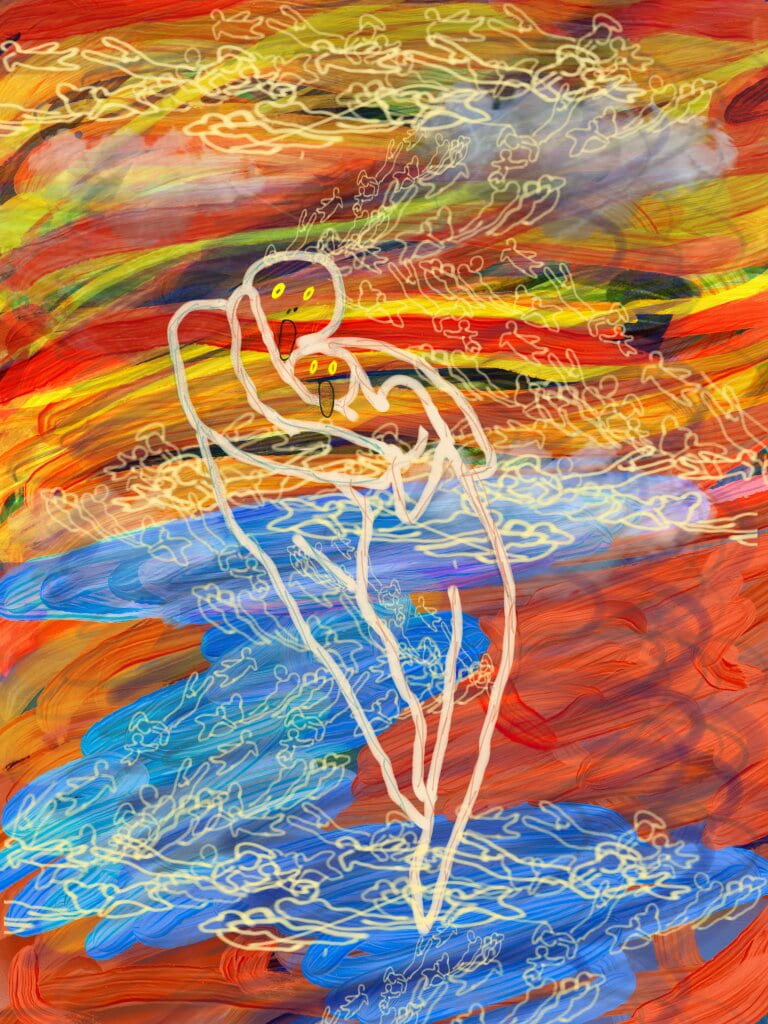

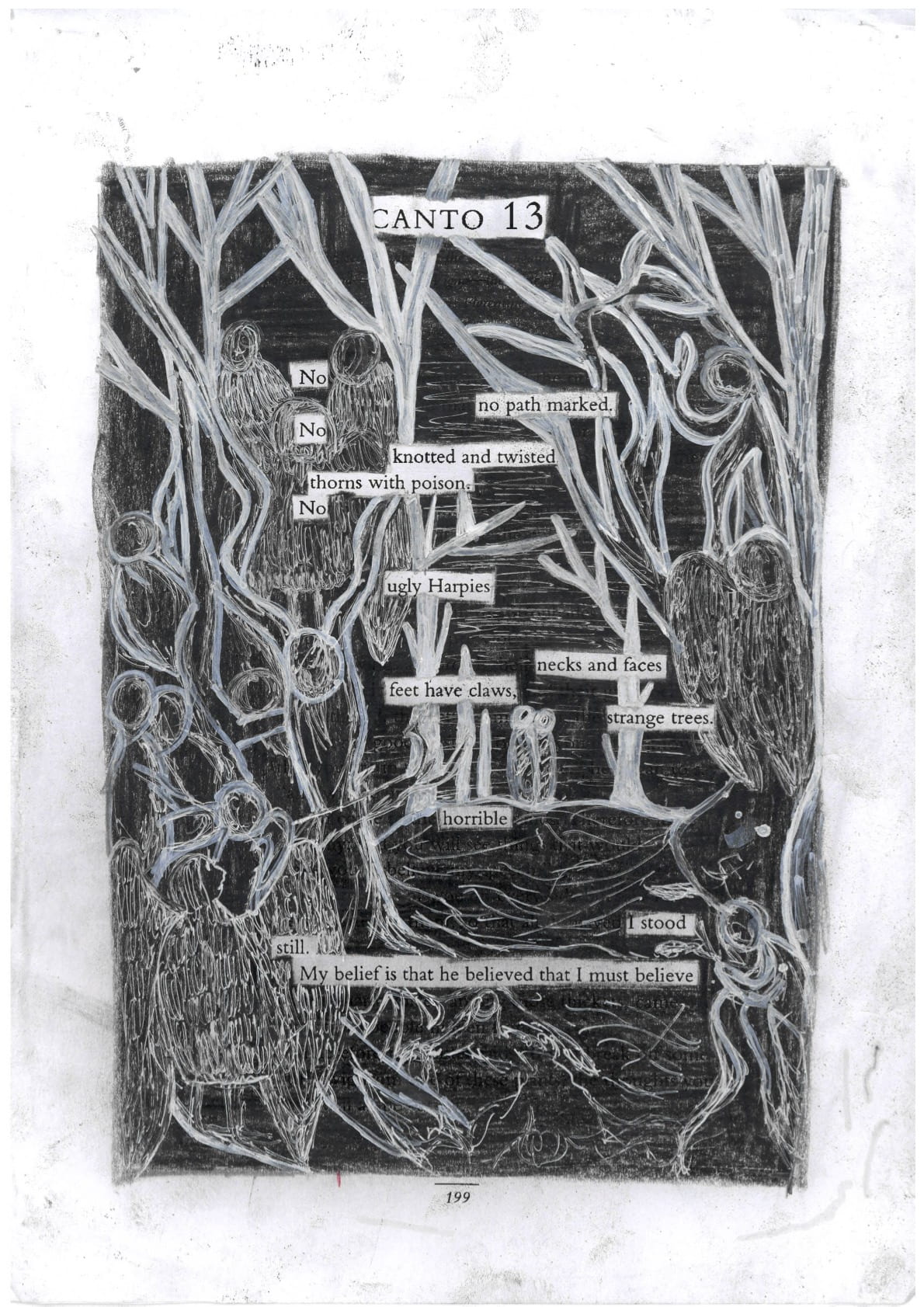

CANTO 13

Canto 13 begins with Dante and Virgil entering a poisoned forest, with Harpies perching on the branches. Dante hears lamentations of pain, but he cannot find the source of the sound until he discovers that the sinners have become the trees, punished to be fed on by harpies for all eternity. I chose to re-image this canto because I was intrigued by Dante’s description of the forest and the visceral image of the horrific punishment endured by those who commit suicide.

In the process of researching and re-imagining this Canto, I hoped to draw insight into how this Canto fit into the entire text, particularly with regards to immortalization and memory. This is one of the many instances where Dante tempts the sinner into sharing their story through the promise of glorious immortalization, where the sinner’s real ‘truth’ is revealed. With this in mind, I am interested in Dante’s text as a strategy of liberation – not only is the sinner liberated from being merely identified by his sin through Dante’s recording of his story, but his soul is also emancipated from its roots in the tree. On another level, Dante himself is liberated from the despair of hell by writing and recording this story. Due to these complex intersecting layers of memory, history and stories, I saw a need to combine multiple art and aesthetic forms for this creative re-interpretation.

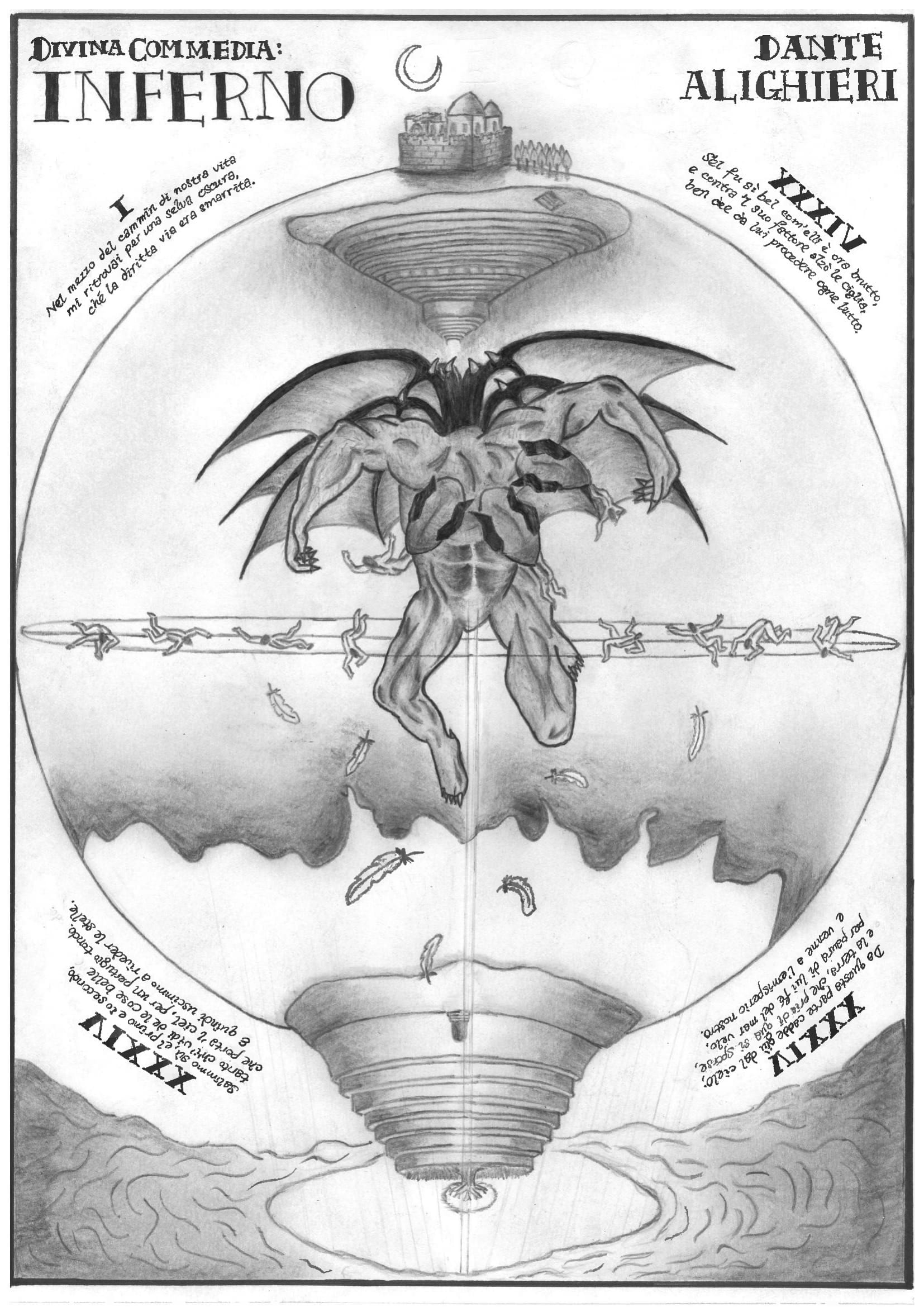

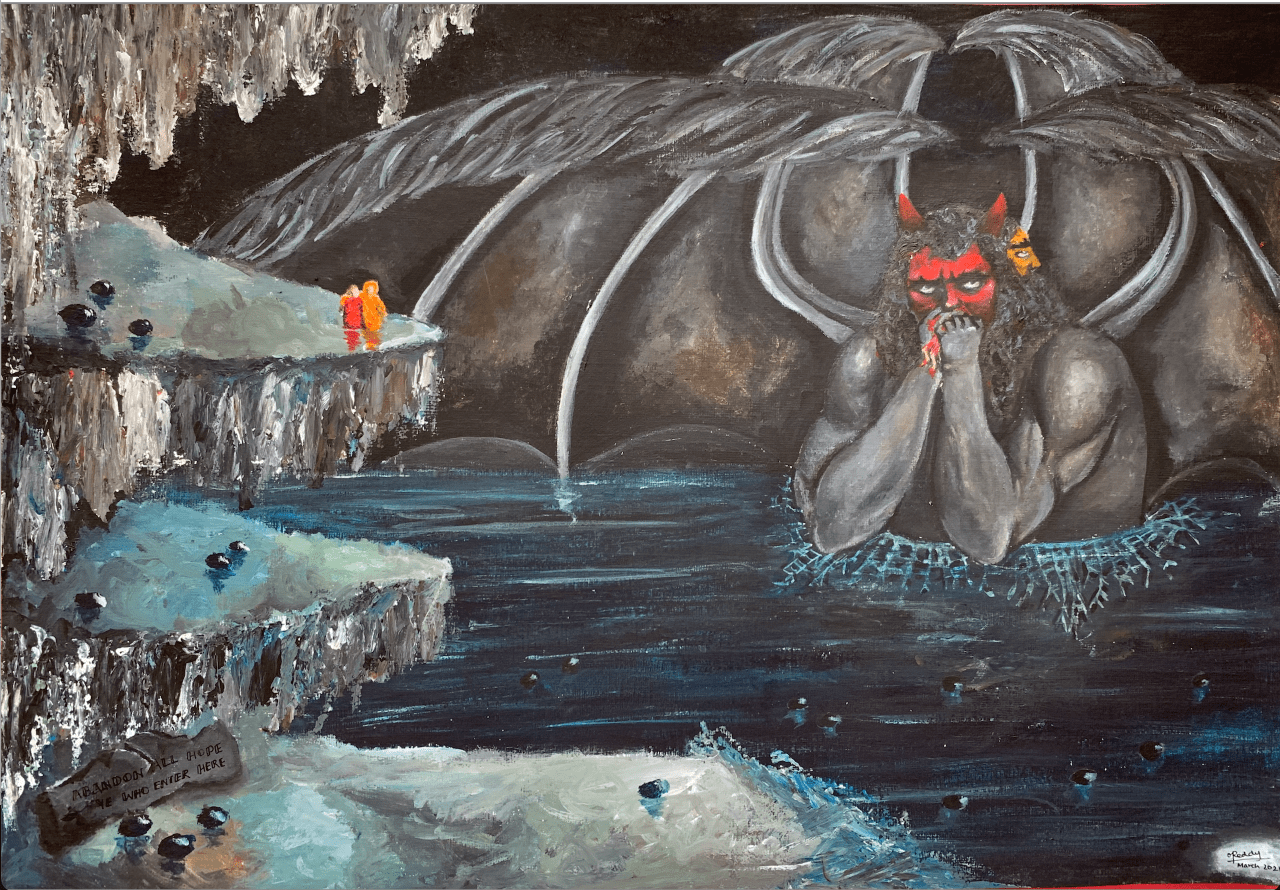

CANTO 34

In Canto 34 of Dante’s Inferno, Brutus, Cassius, Judas, and Satan are imprisoned in the Ninth Circle of Hell for their treachery – Judas and Brutus for betraying Caesar and Rome, Judas for betraying Jesus, and Satan, the ultimate sinner, for opposing God.

Dante’s Satan – A Moving Image, by SIDHARTH PRVAEEN (’21).

I chose to create an animation that depicts Dante’s Satan as he is described in Canto 34. The piece features Satan with three heads, a pair of wings and a beating heart. The head in the middle chews Judas, the one on the left, Brutus, and the one on the right, Cassius. To accentuate the nature of their sins, I borrowed the contrapasso elements from the ninth bolgia and the violence-against-God subcircle and weaved them into my animation. I also wanted to expound on the idea that we had discussed in class about Dante’s Satan as punishment but also the punished. As for the background music, I reversed Sunn O)))’s song Báthory Erzsébet to get the unsettling, disturbing sounds that I added to my animation. The track has a dark yet powerful energy and it seemed apt to me that in a space that punishes and disempowers Satan, the song’s reverse would play in the background.

My postcard evokes Dante’s completed imaginative vision of the afterlife. It can be viewed from both portrait (upright / inverted) and landscape perspectives. The postcard’s interpretative nature expresses the commedia in the Inferno as an immortalization the word of the divine (audaciously so through the words of Dante the poet) that is at once elusive in its reference to the source of evil and clear in the call for recognition and rejection of sin. The absurdity of the postcard compels its recipient to view the world through Dante’s critical humour, albeit in another time and space.

I have chosen to create a medieval manuscript page imitation, completed on paper using pencil and ink. It references the opening and closing Cantos (with direct quotations) to Dante’s Inferno, and draws inspiration from artworks on the mapping of Dante’s hell, fallen angels, and Da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man. Aside from a broad overview of the pilgrim’s journey, this creative piece is most concerned with Lucifer, who was very much diminished and glossed over in the text. This manuscript imitation identifies Lucifer as the pivot that holds together Dante’s proposed structure of the universe according to his theological ideas. The piece can be flipped upside-down. By flipping it anticlockwise, the continuity in the quotes and the grandeur of the pilgrim’s journey can be more keenly felt. In the inverted perspective, the motion of Lucifer’s fall from Heaven and grace, enhanced by the superimposed drifting feathers, is immortalised.

My decision to paint Dante’s and Virgil’s encounter with Satan in Canto 34 after their long and arduous journey through hell is rooted in my fascination with Satan’s unusual presentation. In the popular culture of the 21st century, Satan is portrayed in a seemingly glorified light and regarded as the ‘king of hell’: someone devious, scheming, and to be greatly feared. However, in Inferno, Dante brings to life an almost pitiable version of Satan in his work’s anti-climactic ending. The devil is regarded as “the emperor of the dolorous kingdom” (34.28), the most damned and pathetic sinner to be sentenced to eternal punishment in hell. I drew inspiration from Gustave Doré, one of the most widely known and celebrated illustrators of Inferno for my painting. Doré’s depiction of Satan in this sphere of suffering encapsulates the image that came to my mind upon reading this Canto: one of absolute isolation and sorrow.

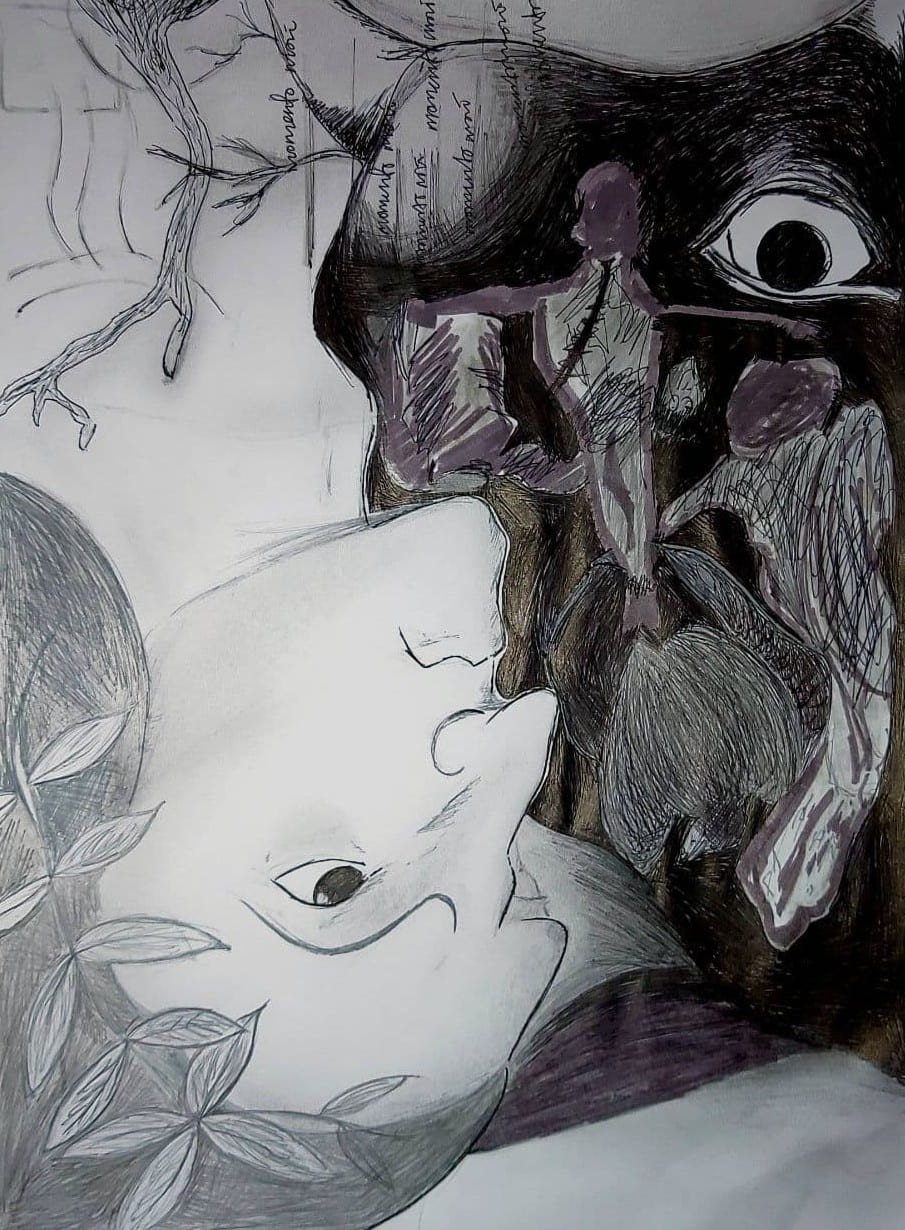

This project is an exploration of centring what is within the margins, and bringing new knowledge to light. It attempts to illustrate details and motifs that relate to Dante’s growing consciousness of sin, having reached the end of the journey in Inferno. This project also seeks to explore the relationship between Christ and Hell. As we come to discover, Hell is His design wherein His standards go forth.

The form of a portfolio intends to show the process of creative exploration, somewhat like Dante’s journey through the various layers. In attempting to visually map what I think Dante sees, I am also hoping to touch on questions of authorship. Much like the intertextual motifs in Inferno, our ideas are not wholly our own, and our recreations / imagined realities are not wholly novel. Where do we draw them from, and what do we hope to achieve? What and how do we see?

REFERENCES

Alighieri, Dante. The Divine Comedy of Dante Alighieri: Inferno. Translated by Robert M. Durling. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996.

IMAGE CREDITS

[Featured Image] Dante Alighieri, Inferno, trans. Robert Durling (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996). ISBN: 978-0195087444.

CONTRIBUTED BY DR. EMILY DALTON, TOH HONG JIN (’23), VIVIEN SIM (’24), ASHLEY SIM SHUYI (’22), SIDHARTH PRAVEEN (’21), YAP JIA YI (’21), OSHEA REDDY (’24), & SIMONE TAM (’22)