| Category | Text |

| Form | Play |

| Genre | Tragedy |

| Author | William Shakespeare |

| Time | Between 1599 and 1601 |

| Language | Early Modern English |

| Featured In | Death, Mourning and Memory in Medieval Literature (YHU3345) |

The Tragedy of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark, or quite simply, Hamlet, is William Shakespeare’s longest play and one of his most famous tragedies, written between 1599 and 1601. Set in Denmark just as the medieval world began to transition to the Renaissance period, the play spans five acts, comprising seven soliloquies and 4000 over lines that cleverly place thematic extremes – for instance, madness and sanity, love and hate, life and death – on both sides of the same coin. Such deliberation over the human condition at once provides insights into the circumstances of its time and imbues the play with a timeless quality, generously allowing for continued retelling and recontextualization.

SUMMARY

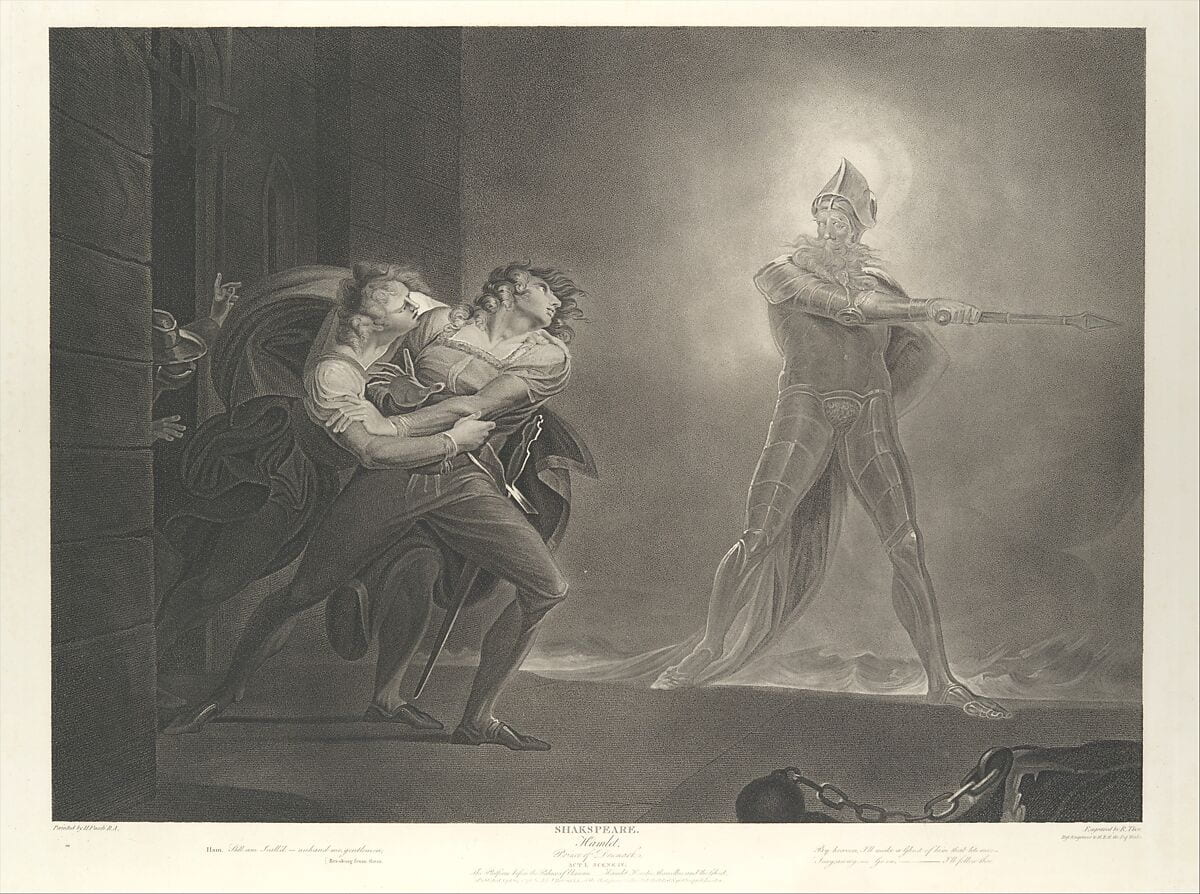

Hamlet, distilled down to the mere unfolding of its plot, tells of Prince Hamlet’s revenge against King Claudius, Hamlet’s uncle, after learning from the ghost of Old King Hamlet that Claudius had murdered the Old King Hamlet in pursuit of “[his] crown, [his] own ambition, and [his] queen” (Act 3 Scene 3, line 55). Duty bound by the ghost’s demand to be avenged, the shaken Prince seeks to verify the ghost’s words, and thereby the presence of a supernatural being, as part of his plan for revenge by putting on an “antic disposition” (Act 1 Scene 5, line 179). Though Hamlet’s subsequent act of madness and erratic behavior – as observed by Ophelia, Hamlet’s love interest, and later reported to her father, Polonius – is initially thought of as a result of distress and grief over his father’s death, Claudius soon becomes suspicious, and observes as Hamlet wittingly deflects Polonius, Ophelia, and his friends Rosencrantz and Guildenstern. Upon learning of the acting troupe brought in by Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, Hamlet stages The Murder of Gonzago, ‘The Mousetrap’ that reveals, to both Hamlet and the audience, Claudius’s guilty conscience.

Gertrude, the Queen, summons Hamlet to her chambers for an explanation as to Hamlet’s offending of Claudius. On the way to her chambers, Hamlet stumbles upon Claudius and, seeing Claudius praying, chooses to withhold his murderous intent for fear that killing Claudius then would send him to Heaven whilst Old King Hamlet stays in Purgatory. In Gertrude’s chambers, Hamlet confronts his mother with her incestuous deed and the truth of Old King Hamlet’s death. The spying Polonius behind the curtains, thinking Hamlet will kill his mother, calls for help, and is promptly stabbed by Hamlet, who believes Claudius to be in the chambers and who proceeds to audaciously insult Gertrude for her ignorance of Claudius’s depravity. The ghost then appears only to Hamlet to berate him for his inaction and his harsh words while Gertrude, only witnessing Hamlet’s fear, believes her son to be mad.

The simultaneous occurrence of Polonius’s death and Hamlet’s slipping control over his sanity brings about a series of deaths in the remaining half of the play. Ophelia, upon learning of her father’s death, becomes mad with grief and drowns (accidental, or otherwise), causing Laertes much grief. His thirst for vengeance leads him to go along with Claudius’s suggestion to engage in a fencing match with Hamlet using a poison-tipped foil and, if Hamlet wins, to offer a glass of poisoned wine as congratulations. The plan goes terribly awry – Gertrude drinks the poisoned wine as a toast to Hamlet’s initial wins, and though Laertes manages to injure Hamlet as planned, Hamlet wounds Laertes too with the poisoned foil. As Laertes lies dying, he exposes Claudius’s plan, prompting Hamlet to kill Claudius. The play ends with Hamlet begging Horatio not to commit suicide and to tell his story as Fortinbras marches through, taking the crown for himself and ordering a military funeral in honour of Hamlet.

DISCUSSION

Reading Hamlet’s whirlwind of a trajectory as the above summary has done so leaves one bewildered by the many inconsistencies and discontinuities that would appear, at times, irrational if not for Hamlet’s soliloquies. Each of the seven soliloquy expresses Hamlet’s inner psyche at various stages of the play’s development, as Hamlet mourns for and struggles to comprehend the loss of his father that has been complicated and made ambiguous by the ghost, whose presence, claim of murder, and dwelling in purgatory entirely destablize Hamlet’s Protestant beliefs and understanding of reality. Finding himself caught in an aporia, he exclaims to Horatio: “There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio,//Than are dreamt of in our philosophy” (Act 1 Scene 5, lines 174 – 75, emphasize mine). While mourning is a transitive process when loss is definitive and comprehensible, Hamlet’s enigmatic loss causes him to remain in an intransitive state of mourning,1 which he describes to be like a “heartache, and the thousand natural shocks//That flesh is heir to”—for, as he confesses to Horatio, “in [his] heart there was a kind of fighting//That would not let [him] sleep” (Act 5 Scene II, line 4). Hamlet’s bodily description of his conscious faculty – the repeated motif of his “heart,” reference to the “flesh” and his insomnia – presents his intransitive state of mourning to be that of a melancholic2 disposition that infects his soliloquies3. In his fourth soliloquy4, he laments:

To be or not to be, that is the question:

… To die – to sleep,

No more; and by a sleep to say we end

The heartache, and the thousand natural shocks

That flesh is heir to: ‘tis a consummation

Devoutly to be wished: to die, to sleep.

To sleep, perchance to dream. Ay, there’s the rub;

For in that sleep of death what dreams may come,

When we have shuffled off this mortal coil,

Must give us pause. (Act 3 Scene I, lines 57-65, emphasis mine)

Hamlet’s repetition of the words “die (death)”, “sleep” and “dream” in a fervent attempt to draw connections between these notions expresses his struggle to comprehend the mortal condition. Upon suggesting that death is a kind of “sleep” that would forebode unknown “dreams,” Hamlet concludes that it is the feared possibility of “dreams,” of the afterlife that causes a “pause,” an inability (or refusal) to make peace with death. The conclusion of this fear, as hinted by his metaphorical reference to the afterlife as an “undiscovered country” later in this soliloquy (Act 3 Scene I, line 80), is very much born out of his attempt at registering the presence of the ghost that reveals the political corruption in Denmark. Hamlet’s lengthy soliloquizing, then, as both a result of and a cause of his melancholia, not only pushes the physical and temporal boundaries of the stage and provides insights into his psychological state, but also shows how Renaissance thought is motivated by the age that precedes it.

Hamlet’s pause caused by his struggle to comprehend death and the afterlife also effectively prepares the audience for the chain of unnatural deaths that will occur later in Act 5, seemingly perpetuated by an unknown force. As the play develops, Hamlet’s mulling over of divine justice and retribution almost writes itself, with deaths happening spontaneously in a reversal of fortune, as my classmates and I had (mirthfully) concluded below:

Most of the characters’ deaths are unwittingly a result of their misdoings, suggesting the capricious Rota Fortunae5, the Fortune’s Wheel which the goddess Fortuna spins at random, changing the position of those on the Wheel. The medieval and Renaissance period saw the use of the wheel in the “Mirrors for Princes,” a popular genre of writing that sets out advice for the ruling classes on the wielding of power, shifting the Wheel from the Goddess to the hands of humans. For Prince Hamlet, figures of philosophy like Fortune are not personified as divine guides, but rather figuratively addressed:

A man that Fortune’s buffets and rewards

Hath ta’en with equal thanks; and blest are those

Whose blood and judgement are so well commingled

That they are not a pipe for Fortune’s finger

To sound what she please. (Act 3 Scene II, lines 62 – 66)

Here, Hamlet likens Fortune’s control over humans’ “buffets and rewards” to that of a musician playing a pipe, and suggests that humans’ ability to reason and judge frees us from becoming Fortune’s fool. As Hamlet later exclaims, “Call me what instrument you will, though you can fret me, you cannot play upon me” (Act 3 Scene II, lines 353 – 354), seeing Fortune as the mere making of human manipulation, and perceiving himself to be above that. Yet Hamlet himself is also manipulated, as his effort to serve divine retribution (his revenge that results in Ophelia’s undeserving death) in turn provokes Laertes’ desire for revenge against Hamlet:

Our indiscretion sometimes serves us well

When our dear plots do pall; and that should teach us

There’s a divinity that shapes our ends,

Rough-hew them how we will – (Act 5 Scene II, lines 8 – 10)

Whether it is the inevitable submission to the whims of Fortune6 (whereby death is the divine retribution for having sinned, prior to repercussions in the afterlife) or undeserving deaths as a result of human folly (Ophelia’s death, as well as that of Rosencrantz, Guildenstern and the soldiers involved in the war between Denmark and Norway), Hamlet addresses the limitations of letting “your own discretion be your tutor,” wherein our moments of irrationality, although beyond our control, are also part of what “shapes our ends”. Through Hamlet’s consciousness, then, Hamlet goes beyond the singular focus of a revenge tragedy plot to consider the vicious cycle of revenge that interweaves the characters’ (including the barely mentioned soldiers) fate, exposing human reasoning as limited by the human condition which, in effect, presents the dichotomies7 of Renaissance thought.

Indeed, Hamlet’s focus on the individual’s mourning and their positioning in a complex web of human relations allows us to better comprehend the occurrence of mass deaths that often ironically evade our empathy and ability to fully register the gravity of our loss. Hamlet’s continued use of the collective pronoun “we” and “us” in his soliloquies (and his addressing of Horatio) includes the audience, extending the ‘pause’ beyond himself which makes room for “commentary and reflection instead of narration” (Genette Gerard, Narrative Discourse 36). Through the experience of mourning, insights on death very much inform life, for the play, “despite its concerns with death, is bursting with life” (General Introduction 29). With Hamlet’s eventual acceptance – “since no man knows aught of what he leaves, what is’t to leave betimes? Let be.” (Act 5 Scene II, lines 169-170), one is prompted to accept the dramatic portrayal of sentiments – excessive fear, anger, love and hate, mourning and mirth – and failings that are only human, as a form of peace-making with death.

FOOTNOTES

1 Mourning as a response to loss can be transitive and intransitive (“mourn, v.1”).

2 According to Robert Burton in The Anatomy of Melancholia (1883), melancholia is a disposition as much as it is a ‘habit’; in other words, melancholia is an affect that is “an act of Mortality” that manifests as a treatable physical “settled humour” of black bile (93). Hamlet is also described as cloaked in black (Act 1 Scene II, line 77) and he confesses to have already “lost all of [his] mirth, forgone all custom of exercise” (Act 2 Scene II, line 294), both of which are also symptoms of melancholia.

3 Here I refer to his soliloquies that come after his meeting with the ghost.

4 For the purpose of this essay, I focused largely on the fourth soliloquy, for it is in Act 3 where Hamlet is most unsettled, having confirmed the presence of the ghost.

5 The Rota Rotunae was greatly popularized for the Middle Ages by its extended treatment in Boethius’s Consolation of Philosophy, and was widely used as an allegory in medieval literature and art to aid religious instruction.

6 Charles M. Radding states in his article ‘Fortune and her Wheel: The Meaning of a Medieval Symbol’:“If the popularity of Fortune in the central Middle Ages does not reflect a new social reality, then it is likely that it was meant to suggest [that] the operation of a force distinct from necessity and also (one might add) from divine justice… the meaning of the Wheel of Fortune is thus quite general: that everyone in human society is subject to the whims of Fortune, that not all of the world’s gifts or the world’s tragedies are deserved” (133).

7 That is, the extremes of reasoning and faith. The opposing ends of Renaissance thought presents either an entire lack of faith in the divine (as proposed by the philosopher Edward Herbert of Cherbury) or, according to Blaise Pascal, total disbelief in the human ability to understand the world with certainty (Fieser).

REFERENCES

Burton, Robert. The Anatomy of Melancholy. Claxton & Co. 1883. Internet Archive, urn:oclc:record:1039522579

Fieser, James. “Renaissance and Early Modern Philosophy.” The History of Philosophy: A Short Survey, 2020, https://www.utm.edu/staff/jfieser/class/110/6-renaissance.htm

Genette, Gerard. Narrative Discourse: An Essay in Method. Translated by Jane E. Lewin, Cornell UP, 1980

Radding, Charles M. “Fortune and Her Wheel: The Meaning of a Medieval Symbol.” Mediaevistik, vol. 5, Peter Lang AG, 1992, pp. 127–38, http://www.jstor.org/stable/42584434.

Shakespeare, William. Hamlet. Bloomsbury Arden, 2016.

“mourn, v.1.” OED Online, Oxford UP, March 2021, www.oed.com/viewdictionaryentry/Entry/11125. Accessed 5 March 2022.

CREATIVE INTERPRETATIONS

The following creative projects, produced for the course on Death, Mourning and Memory in Medieval Literature, offer further perspectives and insights on Hamlet and its thematic concerns:

IMAGE CREDITS

[Featured Image & Fig. 1] http://www.strangehistory.net/2014/11/17/daily-history-picture-playing-medieval-chess/

[Fig. 2] https://www.gla.ac.uk/myglasgow/library/files/special/exhibns/chaucer/works.html

[Fig. 3] https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_1873-0809-801

CONTRIBUTED BY YAP JIA YI (’21)