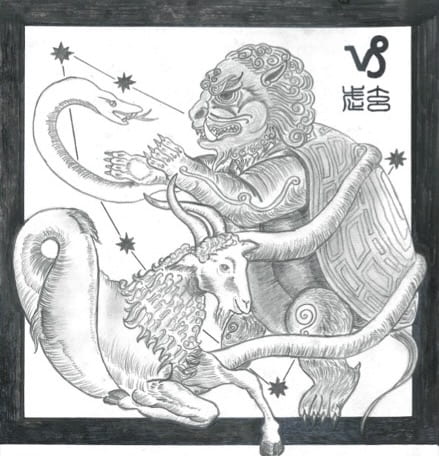

Having encountered many fantastic creatures in various medieval manuscripts, I endeavoured to look beyond to the illusory beasts in the heavens for this creative bestiary entry. Completed with pencil and ink on Bristol paper, the Capricornus-Xuanwu is an imaginary composite creature comprised of the Capricorn from Mesopotamian and Western cultures, and the Xuanwu (玄武) from East Asian culture. The main reason for bringing these existing creatures together into one is their shared position in the night sky—both are represented as constellations with some common stars, and while the bestial forms which these stars have gone on to take may initially seem extremely different, a closer look at some of the tales and accounts of their traits and symbolism reveals surprising parallels between them. This is also an exercise after the medieval bestiary’s tradition of including animals and creatures from drastically distinct cultures and locales, including attempting to synthesise accounts from their place of origin with prevalent medieval beliefs and doctrines.

The Capricornus, or Capricorn, is well-known as an earth-affiliated, cardinal zodiac sign in astrology and as a triangular-shaped constellation in astronomy since classical antiquity and is most represented as a sea-goat, or a goat and fish hybrid creature. The Babylonians saw it as a symbol of Enki (later known as Ea), the Sumerian god of water, knowledge, crafts, fertility, magic, and creation, who has been depicted with long-horned water buffaloes, a horned crown, and sometimes as a man covered with fish scales. In the Greek and Roman imagination of a sea-goat figure, Capricornus was sometimes confused with Amalthea, the female goat that suckled the infant Zeus after he was saved from his Titan father, and her horn was notably transformed into the cornucopia, or “horn of plenty”; the sea-goat was also sometimes identified as the Greek god Pan, a satyr-like figure that escaped the monster Typhon by diving into the river, causing the bottom half of his body to turn into a fish tail.

In this bestiary entry, the Capricornus is represented faithfully on the bottom left of the framed drawing, with a notable change only in the positioning of its tail. Instead of having it spiral downward and its tail emerge from the back (as seen in Fig. 1), I have decided to draw it such that the entire creature bears closer resemblance to the symbol that denotes it, which I have also included on the top left corner. The symbol has always looked like a pictogram of Capricornus to me, with its “V” shape resembling the sea-goat’s horns and the twirled “S”-like segment resembling its fish tail. The single major change to Capricornus in this depiction is in its tail, which does not end anywhere near its body, nor does its literal end look like a fish’s. Instead, I chose to conflate its scaly tail with the equally scaly body of a serpent, which extends and wraps around the Xuanwu turtle, tying the two creatures together, the reason for which I shall return to shortly. Following the tradition of the medieval bestiary’s inclusion of geometric shapes in their visuals, I have drawn some of the stars that make up the Capricornus constellation in the background. In addition, to emulate the medieval bestiary’s tendency to bring in both divine and strangely contradictory accounts, I have incorporated in the text Capricornus’ mistaken relation with Amalthea and located its astrological elemental affinity of earth in Amalthea’s cornucopia.

Fig. 1: Capricornus. Image taken from Encyclopaedia Britannica.

Fig. 1: Capricornus. Image taken from Encyclopaedia Britannica.

The Xuanwu turtle, also known as Genbu in Japanese, Hyeon-mu in Korean, and Huyền Vũ in Vietnamese, is both a god in Chinese religion and, as Black Turtle / Tortoise, one of the Four Symbols of Chinese constellations. The Black Turtle is also one of the Four Auspicious Beasts in Chinese culture, alongside the Azure Dragon, Vermillion Bird, and White Tiger, and it represents the element of water, the cardinal direction north, and the season of winter. Its name literally translates into “Black / Dark / Mysterious Warrior”. The Xuanwu turtle is associated with longevity, as are many other turtle-like creatures in Chinese mythology that then blur together into a single entity, such as Ao—a giant turtle whose legs were used by the Chinese mother goddess Nüwa as pillars to support the skies, and Bixi—a dragon with a turtle shell that tends to be used a decorative plinth for commemorative and funeral steles. This figure is frequently depicted not just as the Black Turtle but also one entwined by a snake, both of which represent the god Xuanwu’s stomach and intestines respectively, which according to legend, were dug out by him to be washed free of sins. After Xuanwu became a deity, his stomach and intestines turned into the aforementioned creatures. These demonic beasts caused such widespread harm that the god Xuanwu had to subdue them, and upon doing so they turned into the god’s subordinates and in a way, his iconography as well.

In the bestiary entry, Xuanwu’s name in Chinese characters is included on the top left corner of the framed drawing as well, oriented from right to left and written in the style of the Chinese seal script. The creature itself is portrayed on the right portion of the frame, upright and interlocked with a serpent, now a part of the Capricornus’ fish tail. The reason for this is to highlight their common hybrid nature and elemental affinity. The Black Turtle itself is drawn with a great degree of artistic license, since it has often been a hybrid of the turtle with various monstrous animals like the dragon and snake. The choice of making it half-lion is in large part due to my being inspired by the lion turtle creature (see Fig. 2) in a popular animated series, Avatar: The Last Airbender, which was itself inspired by the Xuanwu and likely its physical proximity as a stone statue and guardian to the stone lions also found protecting ancient Chinese temples and palaces. The regal and divine fusion of the dragon, lion, snake, and turtle also seeks to invoke the distant but nonetheless interesting resemblance to the French mythological creature of Tarasque, said to have been tamed by Saint Martha, which would geographically draw the Xuanwu closer to the cultures that inspired its astronomical counterpart of Capricornus.

Fig. 2: Lion Turtle. Image taken from Avatar: The Last Airbender Wiki.

Fig. 2: Lion Turtle. Image taken from Avatar: The Last Airbender Wiki.

Overall, this bestiary entry manuscript page presents a juxtaposition of Western and Eastern cultures through their two fantastic beasts and associated legends and symbolisms, based upon how they gazed, imagined, and projected their values and beliefs onto the same part of the night sky. Yet this juxtaposition only reveals that the opposition between the West and East is in fact much more unstable than it seems, with many parallels and similarities amidst their apparent differences. This unsettling of binaries is also prominently invoked through the similar hybridity inherent to these beasts. They may ultimately just be illusory creatures, but taken as one, their boundary-transgressing natures very much highlight the limits and transience of human meaning-making and categorisations.

What seems to be a giant fish represents a whale in the process of toppling a boat.4

What seems to be a giant fish represents a whale in the process of toppling a boat.4

Fig. 1: Capricornus. Image taken from Encyclopaedia Britannica.

Fig. 1: Capricornus. Image taken from Encyclopaedia Britannica. Fig. 2: Lion Turtle. Image taken from Avatar: The Last Airbender Wiki.

Fig. 2: Lion Turtle. Image taken from Avatar: The Last Airbender Wiki.