| Category | Motif |

| Featured In | Medieval Romance: Magic and the Supernatural (YHU2309) |

Prophecy or revelation in medieval romance is the process by which some piece of information is introduced into the minds of characters through divine, mystical, or otherwise unexplained means. The means by which characters receive prophetic knowledge varies widely: sometimes it reveals itself in the form of dreams, while at other times, characters are simply able to perceive truths that remain invisible to other characters. These revelations can be seen across medieval romance. In Gottfried’s Tristan, for example, Queen Isolde is seen “consult[ing] her secret arts (in which she was marvellously skilled);” soon after, “she saw in a dream that things had not happened as rumoured” (Strassburg, 164). In this case, a clear attribution to magic is given. Queen Isolde, whose affinity with magic was earlier suggested by her healing ability, calls upon something that is not subject to conventional rationalisation, in order to uncover the trickery concocted by the young Isolde’s suitor.

Depictions of prophecy or revelation are not always so explicit, however. Within Marie de France’s Lais, for example, Guigemar’s secret lover says “Fair sweet friend, my fearful heart/tells me I’ll lose you, that we’ll part” (Marie de France, Poetry, Guigemar 547-8). It is debatable as to whether this even counts as prophecy, as it is certainly possible that the lover says this because she intuits her husband’s growing suspicion from external actions. Nonetheless, the text does not dwell on the reliability of the information, instead focusing on how the characters behave in response. The premonition prompts the two to create symbols of each other’s loyalty. Surely enough, the couple is found out that same day and the story proceeds with these tokens at the centre of their relationship.

Contrasting these two cases specifically, we begin to see differences in the implementation of the same phenomenon. In Tristan, the reason for belief is explicated because the text is interested in the psychology of the characters (Gottfried’s text reflects the interests of 13th century humanism in epistemology and in human nature). The text, after all, details the encounter of two lovers who defy customs in the name of love. In Guigemar, on the contrary, the love relationship is manifested through actions and external symbols, and the narrative is more concerned with the fulfilment of the romantic tropes of promises and restoration than with the psychology and intentions of its characters.

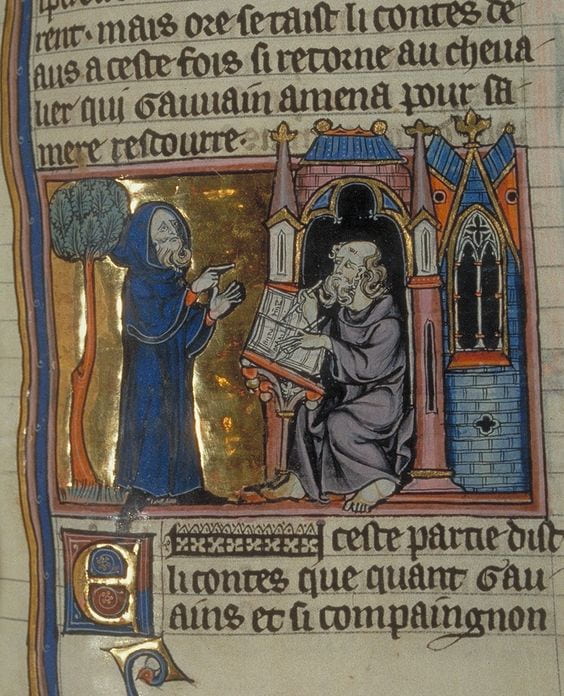

We see, then, that instances of prophecy show something about the relative priorities of each text. This is because from a literary standpoint, prophecy can be seen to represent an almost metatextual aspect of the text; it is often effectively a manifestation of authorial intent. Often we see in Le Morte Darthur that characters are almost puppets of prophecy, such that the author can manipulate their actions simply by introducing prophetic voices—as in the case of Sir Lancelot, who enters a castle for this reason alone (Malory, 390). When circumstance proves insufficient, prophecy can be introduced, and it is in these gaps that we may infer the concerns of the texts.

REFERENCES

Gottfried, & Hatto, A. T. (1972). Tristan: With the surviving fragments of the Tristran of Thomas, newly translated. Penguin Books.

Malory, T., & C., F. P. J. (2013). Le Morte Darthur. D.S. Brewer.

Marie, & Gilbert, D. (2015). Marie de France Poetry: New translations, backgrounds and contexts, criticism. W.W. Norton & Company.

IMAGE CREDITS

[Featured Image & Fig. 1] http://www.lancelot-project.pitt.edu/LG-web/Arth-ME-SV/MerlinComp-NoBL.html

CONTRIBUTED BY ADAM CHRISTOPHER CHAN (’25)