CREATIVE PROJECT BY JODY LIM (’25)

Panda

Visual Art / Literary Art

Creative Bestiary Entry

Real and Imagined Animals in Medieval Literature (YHU2330)

2023

THE MEDIEVAL KINGFISHER BESTIARY

FOLIO III

The panda, called bear-cat in Cathay, is closer to man than cat. It is a giant black and white beast with six-fingered hands. Instead of meat, it devours trees and its presence can be indicated by the crashes of falling trees. The panda gives birth to twin pure black cubs and must paint them white. When the mother panda runs out of paint, she leaves them black and white. She is impatient and has no foresight. She disgracefully tries to become what she is not. For we are his workmanship, created in Christ Jesus for good works, which God prepared beforehand, that we should walk in them. (Ephesians 2:10) Thus, her dissatisfaction will never be sated, for her and her cow-like spawn. As punishment, she sleeps but can never rest and her eyes grow larger and darker with fatigue.

Artist’s Remarks

I chose the panda as it was an Asian animal that medieval Europeans would have never seen. Indeed, knowledge of pandas was only introduced to Europeans when a Vincentian missionary, Armand David, came across panda furs in 18691. Thus, the panda was reminiscent of the bestiaries of real-life African animals like the elephant and crocodile. I wanted to try and reimagine the panda according to the traits that would stand out to a medieval European. I tried to make the description of such an animal seem mystical and uncanny.

The first sentence was an intentional way to set up the exploratory and mystical tone. The first sentence stated “The panda, called bear-cat in Cathay, is closer to man than cat.” First, I wanted to add an element of foreignness through the translation, which is usually from classical languages like Latin or Greek, as seen in the Ape, Elephant, and Tiger bestiary entries. Since the panda is from China, I decided to make use of its original name xiong mao (熊猫), which translates literally to bear-cat. For China, I decided to call it by its medieval name, Cathay2. However, I wanted to lean into a panda’s similarity to humans which this translation did not cater to. Thus, I also made a point of pulling away from the original translation and highlighting the panda’s perceived similarity to humans.

I described the panda as more human-like to break down the animal-human boundary, which is an element I particularly liked in the bestiaries we studied in class. I recently learnt about pandas’ opposable thumbs, which inspired me to focus on its hands3. I thought it might be interesting to think about an animal’s morphological similarities to us, such as the panda being able to pick up bamboo, while being startlingly different — having paws and the thumb being the sixth “finger”. Thus, I highlighted this in its description, referring to its paws as “hands”. I tried to be more intentional in the first illumination of the panda by recolouring a bestiary of a bear while adding on detailed six-fingered hands, with knuckles and fingernails. In the second illumination, I also depicted it holding a paintbrush while sitting down. This action was human-like and could very well be of a man painting as well. Thus, this illumination further served to interrogate what it means to be human. Overall, the panda was depicted as extremely close to humans, both in certain physical features and in behaviour.

Next, I tried to reinterpret bamboo as a food source for pandas. Bamboo would be a foreign plant to medieval Europe and I thought trees would be a good proxy for them. This is also interpreted in the illumination through the panda licking the tree stump.

Then, I included a short story about a mother panda and her painted cubs as the author’s primary method of distancing pandas from humans. Her cubs were born pure-black, giving them a visual difference from a white medieval European infant. The mother tried to make them more human-like through painting them white. However, she ran out of paint and the narrative denounced her as “impatient” and having “no foresight”. The emphasis on her bad character seemed to suggest that her negative traits are the ones keeping her and her young from this elevated pseudo-human state. Thus, humans were implicitly placed on the pedestal again even though they were born human. The illumination went one step further in highlighting the panda’s negative traits, and painting the mother panda as being neglectful. Abandoning and turned away from her half-painted cub, she started painting another. Thus, this depiction further condemned the panda.

Going further into the distancing tactics, I placed the Ephesians 2:10 bible quote for another angle of distancing the human from the animal, through reaffirming their biological difference. The panda was “disgraceful” in her attempts to uplift her offspring beyond their biological form and the narrative denounced them as “cow-like spawn”. This suggests that the panda should just be happy in her station in life.

However, a sense of unresolved dissonance was created through these paradoxical distancing techniques. On one hand, the mother panda was vilified for being unable to fully paint her children. On the other hand, the narrator believed one’s physical body to be unchangeable, while modifying the panda’s eyes as punishment. The very existence of the panda as a black and white animal, in fact, reflected a change of one’s physical form. To me, this description was motivated by the almost haphazard way that bestiary writers try to differentiate humanity and animals.

I was heavily inspired by the bestiary of a bear in both my text and my illumination. Firstly, my first illumination is a recoloured and modified version of the Aberdeen bear bestiary4. I kept to the colour scheme of the Aberdeen bestiaries of blues, browns, and golds. As such, the pandas were recoloured as dark blue despite being described as black. Next, the illumination of the bear focused on how the mother bear would lick its young into shape and I wanted to call back to that in my bestiary of a panda bear5. It would not be a stretch to imagine medieval Europeans taking similar inspiration from their knowledge of bears to make sense of a foreign animal like a panda.

FOOTNOTES

1 “Giant Panda,” Britannica, accessed February 13, 2023, https://www.britannica.com/animal/giant-panda#ref280131

2 “Cathay,” Britannica, accessed February 13, 2023https://www.britannica.com/place/Cathay-medieval-region-China

3 Britannica, “Giant Panda.”

4 “Gallery: Bear,” The Medieval Bestiary, accessed February 12, 2023, https://bestiary.ca/beasts/beastgallery171.htm

5 “Bear,” The Medieval Bestiary, accessed February 12, 2023, https://bestiary.ca/beasts/beast171.htm

REFERENCES

Britannica. “Cathay.” https://www.britannica.com/place/Cathay-medieval-region-China. Accessed February 13, 2023.

Britannica. “Giant Panda.” https://www.britannica.com/animal/giant-panda#ref280131.

Accessed February 13, 2023.

The Medieval Bestiary. “Bear.” https://bestiary.ca/beasts/beast171.htm. Accessed February 12, 2023.

The Medieval Bestiary. “Gallery: Bear.” https://bestiary.ca/beasts/beastgallery171.htm. Accessed February 12, 2023.

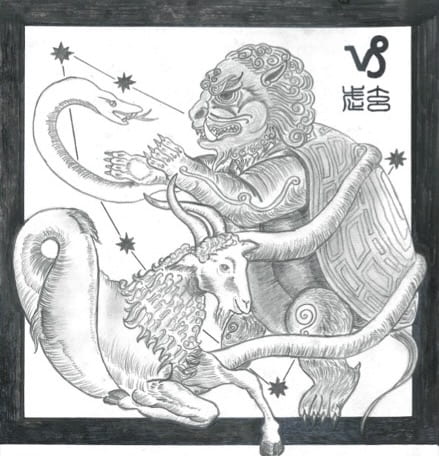

Fig. 1: Capricornus. Image taken from Encyclopaedia Britannica.

Fig. 1: Capricornus. Image taken from Encyclopaedia Britannica. Fig. 2: Lion Turtle. Image taken from Avatar: The Last Airbender Wiki.

Fig. 2: Lion Turtle. Image taken from Avatar: The Last Airbender Wiki.