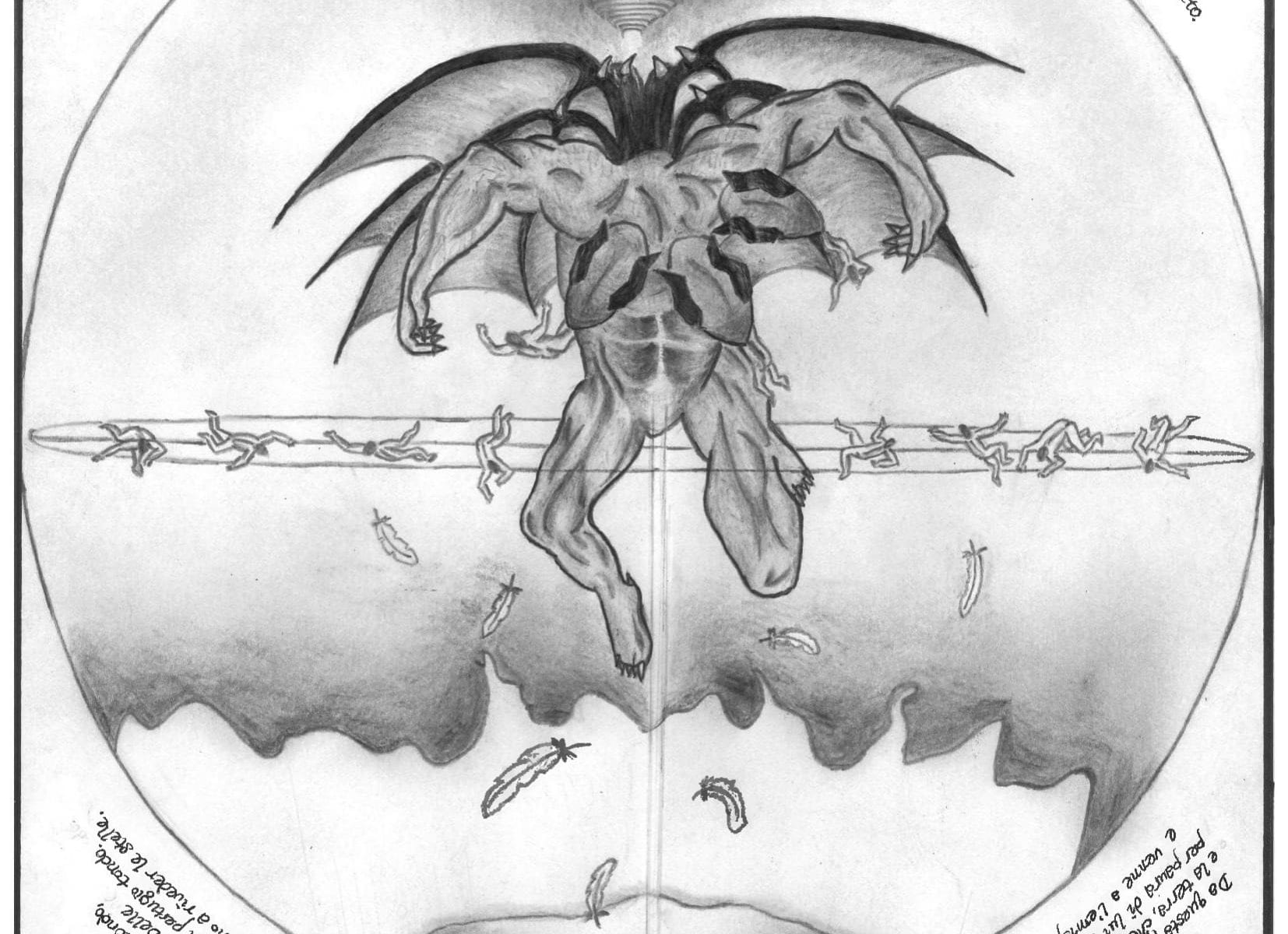

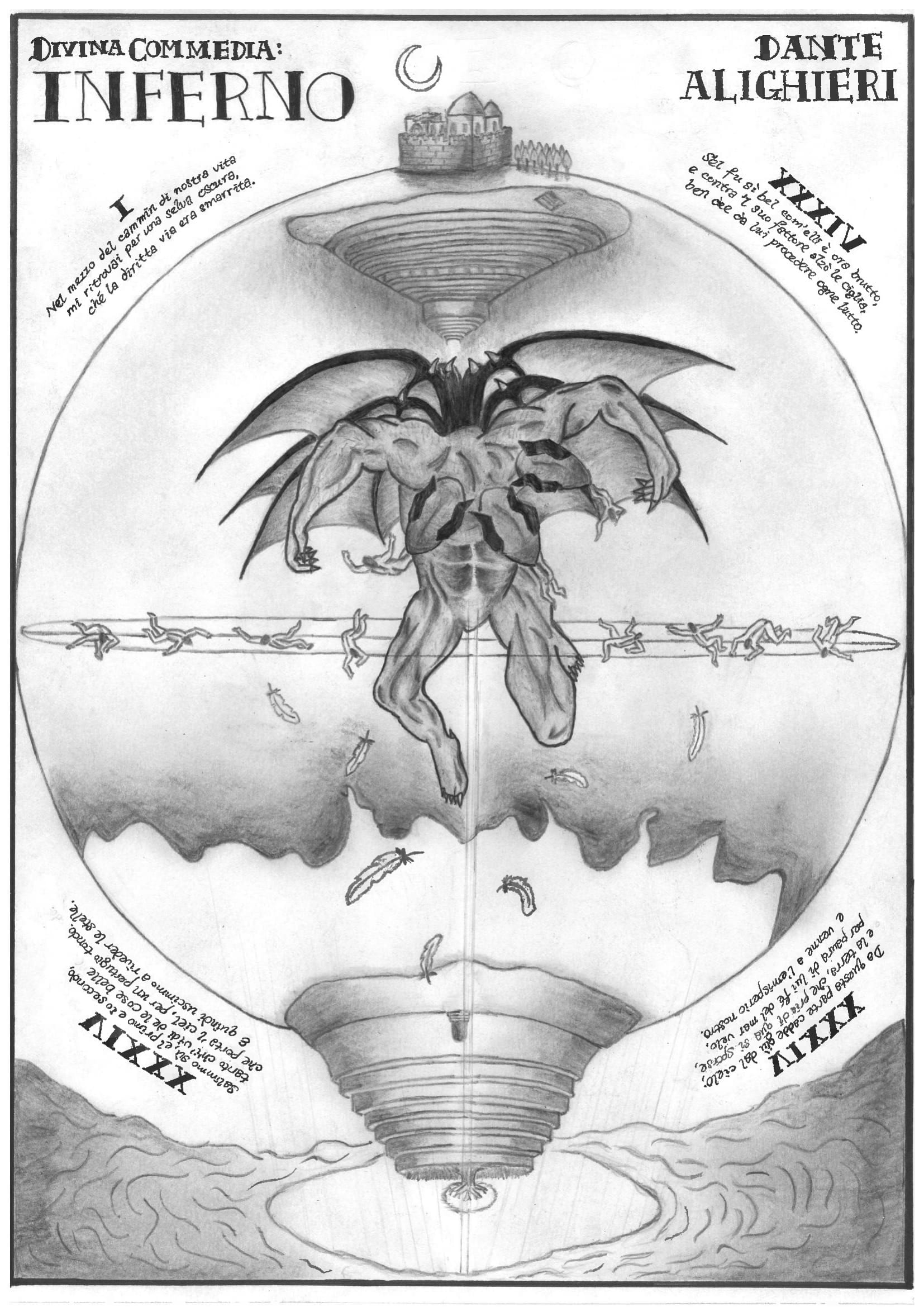

My creative adaptation retells Audelay’s Three Dead Kings in the form of a four-verse, three-part choral piece sung a capella, without instrumental accompaniment and in the style of the chapel. The piece borrows its title and melody from John Henry Hopkins Jr.’s popular Christmas carol, “We Three Kings”, whereas the arrangement and lyrics are original. Although the nineteenth century carol is considered a modern work, it is able to retell an old story through a music style reminiscent of the medieval period. Likewise, my creative adaptation aims to remain faithful in spirit to the original text. Primarily, it is concerned with the danse macabre of Three Dead Kings and seeks to explore and enhance it in a meaningful manner.

Choral pieces are often split into four parts. However, this adaptation is sung by a trio to emphasise the number “three” and to make it seem as though it were the three dead kings (and the three living kings) themselves singing. Correspondingly, the first three verses each represent one of the titular dead kings’ voice and perspective. Although restrictive, I have chosen to keep mostly to the structure of the original carol, with each verse containing five lines observing an AABBA rhyme scheme and an “eight-eight-four-four-six” syllable allocation. This is done in hope that the resulting piece remains as memorable instead of being convoluted and forgettable, so that the memento mori effect of Three Dead Kings can be maximised for the listener. The form of a choral piece also requires a closing segment, which is the reason for an additional fourth verse on top of the three dead kings’ individual “airtime”. This final section serves to tie the individual kings’ messages together for a stronger, single collective message to be communicated. A refrain runs after every verse that represents the living kings’ perspective in the text and to provide a temporary relief of tension from the more serious nature of the dead kings’ words. The individual dead kings are fleshed out effectively in the choral piece through different lyrics, messages, tone of language, mood, and for music, different rhythms, harmonies, and dynamics. In the original text, the most apparent distinction between the kings could be seen from their physique and emotion, reinforced by their living counterparts’ similar reactions if we understand them as the “merour” of each other, as suggested by the third dead king (Line 120).

The first verse’s lyrics focus mainly on bringing out the first dead king’s declaration of their identity—this very act reinforces the lack of remembrance for them (“Honoured not”) and the lack of even the time and “worth” for their living descendants to do so. This sadness of this reality is emphasised through the sibilance in “sorrowing, sighing, seeming”, and the message of the first verse thus hinges on the call for their descendants to notice them (“Lo, behold”) after witnessing them, and remember them thereafter (implied from the dead king’s sorrow at being “[h]onoured not”). This call for the dead kings to be looked upon also directly evokes the memento mori agenda of the text and my adaptation. As the opening and declaration of the bizarre encounter, the music is set to mezzo forte to sound sufficiently solemn for an impression to be made, and yet not overly harsh, so that the weight of the words of grief, “sorrowing, sighing, seeming”, can more effectively convey the extent of the sorrow felt by the first dead king. In terms of technical details, the piece’s triple metre (Time Signature of 3/8) helps to set a waltz-like rhythm that immediately sets the tone for the danse macabre literally, while the minor key, the genre of choral music, and reverberating vocals (enhanced by a concert hall effect) all help to establish the encounter as something both divine and ghastly. Following the first verse, the refrain is written in the style of the classic mass hymns’ chorus part, expressing feelings of reverence. This is done to portray the perspective of the three living kings, who as per the text, “oche…apon Crist cryde, / With crossyng and karpyng o Crede” (Line 51-52), perhaps out of both fear and awe. The third line alone will be changed for the subsequent refrains to reflect the corresponding living king’s reaction and emotion upon the encounter. Unlike the original text, the corresponding living and dead king’s words are place adjacent to each other in the adaptation to further enhance the mirror effect of this danse macabre and memento mori. For the music of the refrain, the original melody at “our damning plight” is rewritten to introduce a minor chord and chord resolution, primarily to reduce monotony, but it also generates a sense of unease and caution to signal that the encounter with the dead king is real, unavoidable, and ongoing, even with their prayers to Christ.

The second verse focus on the next dead king’s lament of all material things’ eventual ruin by drawing attention to his pitiful and hollow state in death (“Black as night, and barren as dust”), juxtaposed with the material success that he had in life, which was a mistaken obsession (“Astray…from [the] just [way of living]”), and in death seemed only ludicrous (“Gold, I had halls / Wives, I had more!”). As the second dead king was described as “a ful brym bere” (Line 105), almost obnoxious, the music here is set to forte, with the bass vocals lowered in terms of pitch. For rhythm, there is now an accent on the first note of every bar and parts of the verse initially scored as beamed-quavers are changed to long-short dotted notes. The rhythm for this verse thus has a slight swing and comes off as somewhat stately, which further fleshes out the dominant character of the second dead king. The second refrain maintains at forte, with the third line written to sound more like words of rally, mirroring the second living king’s similar strength. The third line is also an allegory to the biblical Exodus to depict more vividly the living kings’ predicament of being trapped in this encounter. Furthermore, the word “slavery” is a double entendre, where aside from referring to their entrapment, also points to the second dead king’s enslavement to material desires, which could possibly—ironically—apply to the second living king as well.

The third verse captures the third dead king’s contempt for others while alive and his retribution in death (“pride I wore” against “[a]ll but fools would bow to me not”). It also contains his haunting message of “Makis your merour be me”, a quintessential quote from the text since it confirms the significance of this danse macabre as a memento mori for the living kings, bidding them to reflect and repent on their actions (“to what [they] ought [to be]”). As the third king is described as frail, “[w]ith eyther leg as a leke” (Line 119), and his living counterpart experienced terror with “[b]ot soche a carful knyl, to his hert coldis” (Line 81), the volume of the music here is set to mezzo piano to express the third dead king’s fearful nature and his demolished pride while in death. The arrangement of the bass vocals and the rhythm returns to that of the first verse, primarily to distinguish from the second verse (and the second dead king), but it also builds onto the waltz-like tempo of the first verse. Along with the lighter vocals, this verse becomes slightly more hypnotic, and its repetition from the first verse creates an ambience that resembles being on a revolving carousel, implicitly evoking the carnivalesque nature of the encounter between the living and dead in the text. The third refrain’s third line is almost identical to parts of the previous refrains—on one hand, it depicts the third king’s desire to flee from this fearful event; while on the other, the establishment of repetition in words and the melody by this point helps to reinforce the text’s danse macabre, suggesting life and death as something circular like a carousel, and something that applies to all.

The final verse, as the closing segment and final reminder of the text’s memento mori, is much more didactic, signified by the direct address and commanding tone of the lyrics, the return of the second verse’ music and rhythm arrangement, and the dynamic of fortissimo. However, it is also a plea for remembrance, seen from the third line’s words “please” and “beseech”, the ritardando, the switch from long-short dotted notes back to regular beamed-quavers, the decrescendo, and the fermata at the word “thee”. The verse ends with accents on the word “Judgment” to close the danse macabre, by warning the living kings to live properly should they desire to avoid punishment in afterlife. The decrescendo and drop in volume from fortissimo to forte then indicate the dead kings’ imminent departure. Unlike the first three verses where the note at the word “O” contains a fermata, the music of the final refrain is not detached from that of the verse to avoid fragmenting the final attempt at sending the text’s overall message across. This union of the verse and refrain in music also symbolises the living kings adopting a “hendyr hert” henceforth (Line 136), with them being on the same page as the dead’s warnings. The change in how they live is further showcased from the humbler and gentler tone of the lyrics in “Guide our journey, kind, and mercy”, which is less sorrowful, less prideful, and less fearful. The original carol’s major chords supposedly sung for the part, “our damning plight”, is then restored for the final refrain to demonstrate an optimistic resolution of the tale, as per the way it ended in the original text of Three Dead Kings.