CREATIVE PROJECT BY DEBORAH JANG

Salmon

Visual Art / Literary Art

Creative Bestiary Entry

Real and Imagined Animals in Medieval Literature (YHU2330)

2023

THE MEDIEVAL KINGFISHER BESTIARY FOLIO V The salmon is a fish that swims in rivers. The salmon is so named because it leaps out of the water and arcs through the air before plunging back into the depths. By this the salmon grows gossamer wings that enable it to climb waterfalls. In the spring, a mass of salmon all together swim upwards, reversing the flow of streams. Bears wait by the banks of the river, and the salmon jump into their mouths, so that the bears grow fat and lazy without lifting a finger. The bears represent the evils of gluttony, whereby one greedy lord profits from the struggles of the masses. There is a story in Ireland of a massive salmon with shining silver scales and large eyes. This salmon contained all the world’s knowledge in its body. It is said that whosoever should eat of the salmon would instantly gain the knowledge of all humankind. This salmon represents King Solomon, whose wisdom surpassed that of any man before or after him, as described in the Holy Scriptures: “And God gave to Solomon wisdom, and understanding exceeding much, and largeness of heart, as the sand that is on the sea shore. And the wisdom of Solomon surpassed the wisdom of all the Orientals, and of the Egyptians; And he was wiser than all men” (1 Kings 4:29-31). And from the wisdom of Solomon this bestiary takes precedent, for “he treated about trees, from the cedar that is in Libanus, unto the hyssop that cometh out of the wall: and he discoursed of beasts, and of fowls, and of creeping things, and of fishes” (1 Kings 4:33).

Artist’s Remarks

This entry takes inspiration from the Irish mythological tale of the Salmon of Knowledge. It follows the structure of a medieval bestiary entry and shows how these intertwine mythology, fact, and religion.

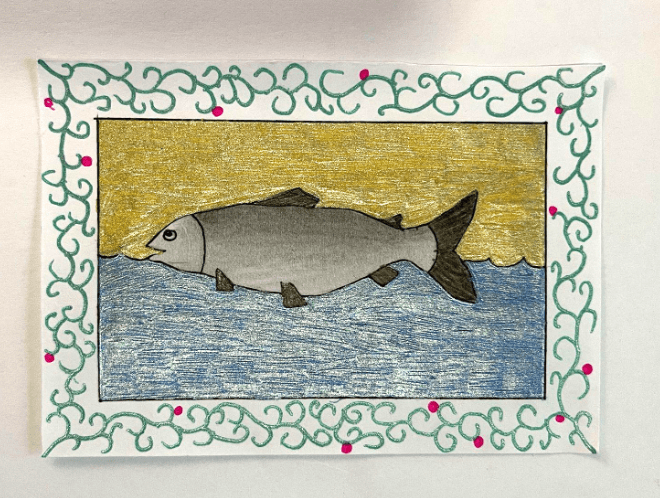

The art is simple, showing a single salmon floating in the water. I chose to use metallic pens to mimic the gold leaf and precious materials used in expensive bestiaries. (As I emptied my gold pen onto the paper, I felt keenly how much I was spending, similar to how an illuminator may have felt when using up gold leaf.) The color palette is limited, like that of an authentic medieval artist, who must mix their own colors. While I did use a picture of a real salmon as a guide, my art skills are not the best, so my fish still looks different from the original, as do medieval artists’ beasts. My fish even has a somewhat expressive countenance; the word I would use to describe it is “derpy.” The frame of vines mimics that of a formal bestiary illustration, which also has an elaborate frame.

The text entry closely follows the observed structure of the medieval bestiary. It begins with etymology and proceeds to list some basic facts. Next, it delves into an involved, unbelievable story, finally ending all anecdotes with a moral tie-in. After learning that the Aberdeen bestiary followed its entry on peacocks with a Biblical quote and a two-page sermon (“Peacock”), I found it appropriate to expand on this format by adding a final paragraph highlighting another relevant verse from the Vulgate Bible.

According to (“Salmon (n.).”), one possible origin of the English word salmon is from the Latin meaning “leaper” or “to leap.” While this is of dubious origin, all bestiary facts are of dubious origin and it seems fitting that something from Celtic (“Salmon Etymology”) or “folk mythology” (“Salmon (n.).”) should end up in a medieval bestiary that references an Irish myth.

The facts are grounded in actual salmon phenomena; salmon are generally known to jump out of the water, swim upstream, and even jump waterfalls. However, medieval observers would have had little knowledge of how these actions are performed, leading to explanations such as “gossamer wings” that they cannot definitively perceive. Bears, too, are known to eat salmon, and by introducing a predator into the entry, it is clearly seen where a salmon’s place in the hierarchy is: food.

The story of the Salmon of Knowledge has many variants, but can be briefly summarized as follows. The poet Finegas caught the Salmon of Knowledge and had his protege Fionn cook the fish for him. However, the hot fat burned Fionn’s thumb and he sucked his thumb, resulting in all the fish’s knowledge being transferred to him. Fionn then became a great man (“The Salmon of Knowledge”, “Why the Salmon?”). My friend discovered this mythical creature while we were writing a different story, but it is such a good example of an odd mythological story from a similar time period that I found it appropriate to include in the entry. What is striking about this story is that the poet Finegas is not angry with Fionn when Fionn accidentally takes the knowledge he intended to have; instead, he was “happy for” Fionn (“The Salmon of Knowledge”). In so many other tales he might have sought to take revenge, but this story has a happy ending despite its twist.

Both the mention of the bears and the story of the salmon of knowledge culminate in moral lessons. The bear’s lesson, that of the greedy lord who profits without putting in the effort, is both a moral tale cautioning against sloth and a commentary on corruption and power. The salmon of knowledge has parallels to the biblical story of Solomon, principally since both are in possession of the greatest knowledge of the world. Connecting the fish to a biblical story serves to grant it legitimacy. It is a unique mix of religion, mythology, and fact. While a bestiary purports to give facts as well as moral lessons, the nature of a medieval writer’s knowledge of science means that fact and fiction become inextricably intertwined, described by Sarah Kay as “a combination of Christian homiletics and early encyclopedism” (Kay 12). I attempted to replicate this by mixing salmon fact and salmon fiction.

Finally, two passages from the Vulgate Bible (The Vulgate Bible 1 Kings 3) are cited, following the format of many bestiary entries we read in class. The first is a simple reference to Solomon’s wisdom, but the second reflects the purpose of a bestiary. Solomon is said to have knowledge of all plants and animals, displaying how vast his wisdom is. Thus, knowledge of plants and animals serves as shorthand for all knowledge. A bestiary, too, is shorthand for all medieval knowledge, whether of science, religion, or mythology. While it is still committed to spreading good morals and religion, as seen by my entry’s acknowledgement that it “takes [its] precedent” from Solomon’s wisdom, it is nevertheless a surprisingly comprehensive look at the state of medieval knowledge and learning.

REFERENCES

Kay, Sarah. “Skin, Suture, Caesura.” Animal Skins and the Reading Self in Medieval Latin and French Bestiaries, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL, 2017, pp. 3–21.

“Peacock.” The Medieval Bestiary, https://bestiary.ca/beasts/beast257.htm.

“Salmon (n.).” Online Etymology Dictionary, 5 Jan. 2022, https://www.etymonline.com/word/salmon.

“Salmon Etymology.” Etymologeek, https://etymologeek.com/eng/salmon.

“The Salmon of Knowledge.” Irish Myths and Legends, http://www.irelandsmythsandlegends.com/the-salmon-of-knowledge.

The Vulgate Bible: Douay-Rheims Translation. Vulgate.org, https://vulgate.org/ot/1kings_4.htm. “Why the Salmon?” Graduate Student Life, University of Notre Dame, https://gradlife.nd.edu/about/why-the-salmon/.