CREATIVE PROJECT BY TAMANE HARATA (’24)

Deer

Visual Art / Literary Art

Creative Bestiary Entry

Real and Imagined Animals in Medieval Literature (YHU2330)

2023

THE MEDIEVAL KINGFISHER BESTIARY FOLIO II There is an animal that is called deer, known for its swiftness, the delicacy of its limbs, and especially its marvelous horns, for so the Greeks named it keraós. While it is commonly assumed that deer are fearful prey, they are extremely keen observers from both close and long distances. Deer can be found camouflaging themselves amongst the naked branches of autumn and winter, or even proudly making appearances in the middle of one’s backyard. Deer seem fearful, yet through both camouflage and public appearance, their gaze will be directed towards us, in other words, Mankind. No matter how well they hide themselves amongst the woods in one’s garden and no matter how far away they may be, Man feels exposed under those black eyes. Man might be tempted to draw the curtains to avoid their gaze, yet their appearances in his own territory fascinates him enough to forget such an option. The sight of their horns and delicate body provokes Man’s inexplicable desire to keep looking at them, while being tormented that he is under watch. The immense glass window of his living room separating his world from their fluctuating territory appears nonexistent in such turmoiled truth. This is especially a constant reminder for a Buddhist Man that no matter how well concealed his evil deeds seem, the Heavens are looking over what he does. There is a saying in Japanese Buddhist traditions, that when Man hides himself in the shade for a long time and hopes to remain in darkness forever, it is only a matter of time until the sun will eradicate the entirety of the shade and expose this Man to the world. This is because the Heavens see through the shade and know the right time to expose him. When one walks around an immense statue of the Buddha in Nara, he will realize the statue’s gaze always follows wherever he goes. The gaze of the deer resembles this. Whether Man encounters deer in a backyard, or within the peripheries of the Buddhist temples in Nara where they follow humans around, their silent gaze will reinforce Man’s awareness of being watched by the Heavens and of the consequences of his attempt to get away with whatever scheme he plans to do. That is perhaps the reason why Man feels tormented under the watch of those deer, becoming overly conscious of what he is doing even if it is not necessarily a bad deed. Man may sometimes wonder why he questions the judgements in the deer’s eyes, for they may only be blankly gazing at him without the knowledge of right and wrong. However, the Buddhist reminder and saying are so powerful that Man cannot make himself indifferent towards the deer looking at him, nor even prevent himself from looking at them in return.

Artist’s Remarks

This is a modern reimagination of a bestiary entry regarding deer from a 21st-century teenager’s perspective. It aims to follow the basic structure of the bestiary, starting from a very brief overview of the animal and the etymology of its name, then elaborating on certain possible tales involving the animal, and finally diving into the religious and moral implications of the animal’s characteristics that are in focus within the entry. In this entry, I chose to develop the underlying concept of the gaze from my own experience with deer. I often encountered them as a teenager inside the backyard garden of our house in Ithaca, New York, as well as in every corner of the city of Nara in Japan. The adolescent perspective of this bestiary entry derives not only from the fact that I was twelve or thirteen when making these observations about deer, but also because I wished to shrink the gap between medieval bestiary entries and my own by refraining from conceptualizing deer in a scientific manner, and instead elaborating on genuine observations the way medieval records seem to convey.

Here, because the most striking thing I noticed about deer in the garden and in Nara was the way they would intensely gaze at humans, I aimed to entangle Derrida’s notion of the “consciousness of being naked” and the knowledge of “[being] seen and seen naked, before even seeing [oneself] seen by [an animal]” (11) with Buddhist sayings about Buddha’s constant gaze. I specifically chose the Buddhist perspective mainly because my teenage self was a Buddhist and the deer found in Nara mostly spend their time inside the confines of Buddhist temples. I have modified the nakedness portion of Derrida’s arguments into a more moral concept because I thought that the preoccupation with Buddha’s gaze strongly resembles the pattern of Derrida’s description of shame and preoccupation with being gazed at by an animal and seeing oneself being seen by that animal. As the latter resonates with “Man’s awareness of being watched by the Heavens” mentioned in my entry, I shall also point out that deer found in Nara’s temples tend to stare at and interact with passers-by very frequently. It is thus said that they serve Buddha in watching over the visitors’ deeds. With this connection between animal gaze (deer gaze) and Buddha’s gaze, I believed this seemed to fit the medieval bestiary entry’s pattern of elaborating on the religious and moral implications or symbolisms of the animal being described. This is where I decided to make a more contemporary entry and transcend European boundaries by shifting to the viewpoint of Buddhist morals rather than merely reiterating the religious and moral connotations of deer in a medieval European context.

For instance, I was able to relate with Derrida’s description of shame under an animal gaze: I felt ashamed to be seen by a deer when I was playing video games rather than doing homework and also ashamed of being ashamed. At that time, because I obviously had not read the Derrida piece, I connected this experience of shame with the Buddhist saying in my bestiary that my family often refers to (especially when I hide the fact that I was avoiding studying…).

As for the visual image, this photograph consists of a picture I took myself in the backyard from our home in Ithaca. Rather than drawing a deer, I chose to incorporate this photograph as I wanted to preserve the medium of photography that connotes a more modern approach to a bestiary entry. Moreover, I found that the deer’s brown color fuses especially well into the color of the branches and the dead leaves, so much so that its black eyes stand out quite strikingly and draw our attention straight towards those eyes. This led me to think of the line “Man’s inexplicable desire to keep looking at them” in my entry and the following paradox that had left me disturbed for a long time: despite the shame and awkwardness in being stared at so intensely for a prolonged period, their wildness and alterity still urge us to meet their gaze and find ourselves in wonder, as though calling forth Derrida’s questioning of “Who was born first, before the names? Which one saw the other come to this place, so long ago?” (18).

REFERENCES

Derrida, Jacques. The Animal That Therefore I am. 2006

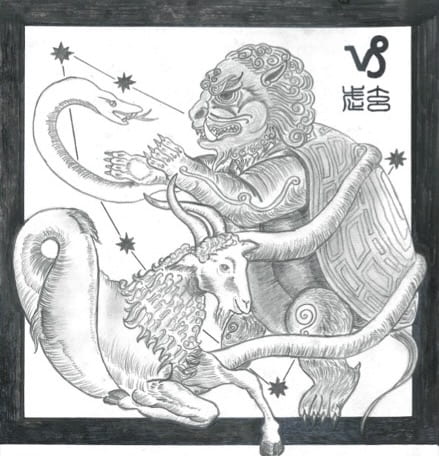

Fig. 1: Capricornus. Image taken from Encyclopaedia Britannica.

Fig. 1: Capricornus. Image taken from Encyclopaedia Britannica. Fig. 2: Lion Turtle. Image taken from Avatar: The Last Airbender Wiki.

Fig. 2: Lion Turtle. Image taken from Avatar: The Last Airbender Wiki.